Like many of our friends and colleagues who edit, write, and teach poetry, the CR staff is often asked about the uses of this craft or sullen art. As we hawk our wares at readings, distribute sample copies at neighborhood coffee shops, or even speak with conference-goers at book fairs, readers either curious about poetry or confused about its relevance to their lives shrug and say some version of, “Poetry? But what does it do exactly?”

One possible answer comes from the elegy, one of the oldest subgenres of lyric poetry. Elegies, from the Greek elegeia or “lament,” ask us to enter into the experience of loss, uniting author and reader in shared expressions of grief. Whether praising the life of a deceased public figure or mourning a private loss, elegies, ideally, bring us closer to consolation by giving a form to grief.

Issue 11.1 assembles a number of powerful, moving, and even unlikely elegies that, as Emily Dickinson put it, “tell it slant.” Among these indirect elegies we find a poem that confronts the tragic early death of poet Jake Adam York through the objective correlative of an upright piano destroyed by Hurricane Katrina, as well as an elegy for the dead exhumed from the cemeteries of San Francisco in the 1930s and ’40s, a period in which the city voted to reappropriate this land for other uses. Read on to discover what our contributors have to say on the subject of loss, and how each poet shaped these losses into some of the most mournful, melancholic, and plaintive poems offered in our pages.

Keith Ekiss on “Burial Fragments”: In Buena Vista Park, on the edge of the Haight-Ashbury district in San Francisco, if you take the path from Haight Street to the top of the hill, you might notice that the gutters along the walking path are made from marble. It seems rich, this marble, a remnant from another era in which public parks were considered civic treasures. And if you stop and look closely, as a friend once told me to do, you might notice inscriptions, names—or parts of names and dates—and bits of phrases that memorialize the dead. These fragments are the remains of cemetery headstones.

In the 1930s and 1940s, after a series of ballot measures and various proposals, San Franciscans, seeing themselves as short on usable land, started eliminating most of their cemeteries, digging up the graves and building new cemeteries south of the city in Colma. Unclaimed headstones and graveyard statuary (the dead could not object) were broken up and “re-purposed” throughout the city, as seawall by the beach and as gutters in Buena Vista Park. There aren’t many names visible, given all that marble, and I like to think the person who laid the gutters, out of some vestige of respect, tried to hide most of the names. In the back of my mind, I was probably thinking of Richard Hugo’s poem “Graves at Elkhorn,” with its commentary on the way cemeteries reveal cultural values, which ends:

The yard is this far from the town because

when children die the mother should repeat

some form of labor, and a casual glance

would tell you there could be no silver here.

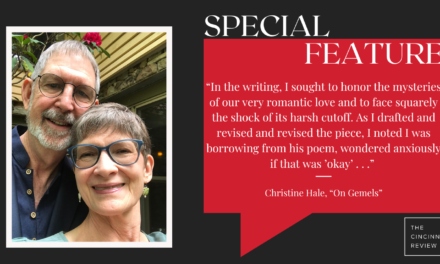

Elton Glaser on “Circuits Open and Closed”: What’s behind this poem never gets into the poem. In April 2011, my wife of forty-two years, apparently in good health, died unexpectedly in her sleep. Ever since then, my own sleep has been erratic. Sometimes I fall asleep at 8:00 and then come awake at midnight, unable to close my eyes again. Variations on that theme make up my nights. This poem probably began with the phrase “my late, abbreviated sleep,” and the images accumulated from that point, prompted by jottings on notecards I’ve kept over the years. The conclusion of the poems returns to its secret source: “I may have come / To the end of something, but there’s no end to the end.” The poem finds its closure, but the hurt never does.

Christopher Lee Miles on “Battle Tank Truck”: This poem is in memory of my brother. He died young, too young. Rather than label the poem “Elegy” and address him directly, or lament him indirectly, my technical purpose was to melt these common elegiac forms of address into the poem itself. I wanted the images, rather than the voice of the poem, to communicate his absence. I wanted the loss tucked into the very structure of the poem. Did I succeed? I cannot say.

Kevin Simmonds on “Upright”: In 2005, the late poet Jake Adam York traveled to New Orleans. He did so shortly after residents were allowed to return following the breeches of the levees during Hurricane Katrina. I’d asked if he would visit my childhood home and see if my upright piano was still there in my bedroom. He kindly said yes and took several pictures for me to see what was left of it and my home. (I was living in Singapore at the time.) That piano meant a lot to me growing up and I wanted to write a valediction of sorts–not only for the piano but for the other losses the water left in its wake. And I wanted to dedicate it to the memory of a warm-hearted, conscious and talented poet who inspired the poem.