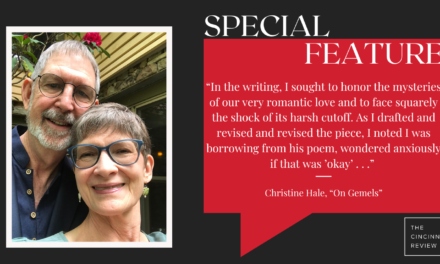

Continuing our series of blog posts from contributors to Issue 17.2, today we have a brief essay by Kaveh Bassiri, who describes his process writing the poems in his chapbook Elementary English, two of which appeared in our fall issue. We’re excited to share this look into the artist’s mind and family history.

Kaveh Bassiri: The poems “Conversation Practice” and “Repetition Practice,” in The Cincinnati Review Issue 17.2, are from my recently published chapbook Elementary English (Anhinga Press). The chapbook is a conversation with my grandmother, inspired by her English language textbook, which she kept on her bedside table, along with her Qur’an, for more than twenty years. As with many Iranians, she was a Muslim who prayed every day, but she never believed in wearing a hijab or in the rule of a religious autocracy.

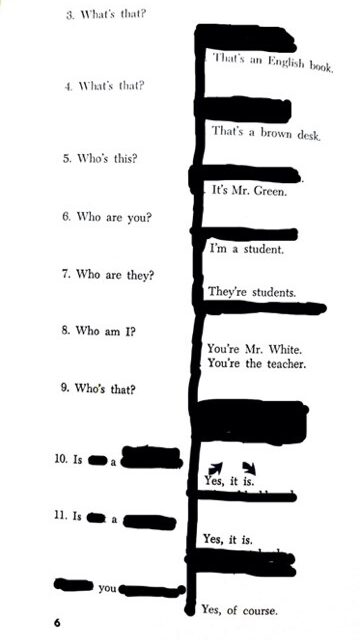

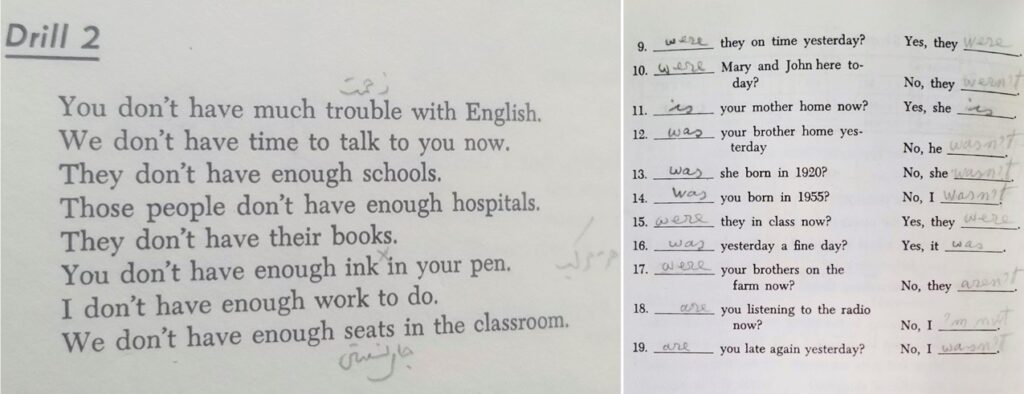

Her ESL textbook was originally prepared by English Language Services for the Foreign Assistance Program of the United States Government. She took it back and forth between Iran and America. On the title page, she had signed her last name mistakenly as Sharib, which reminds me of Sharāb, or “wine” in Persian. She didn’t drink wine, but she loved the frequent use of it in Persian poetry. She also wrote her address, in Persian, as being on “Television Street,” which I don’t recall and is no longer the name of any street in Tehran.

When she passed away, I kept her textbook along with some photos. The book stayed on my bookshelf until sometime later, when I started to look for signs of her. I traced her through her markings, the stains, the words she had translated, and the assignments she had filled in the book. The path also took me back to my own experience of learning English, to Dick and Jane, and to going to Sunday school in Tehran with two American kids in our neighborhood.

So many elder immigrants diligently attend ESL classes, trying to improve their English in order to talk to their grandchildren and to participate in family conversations. My grandmother, who was a high school teacher in Iran, was no exception. How strange to discover that the words she had most often translated were “plan,” “fun,” “problem,” and “trouble.” She had carefully written the Persian translation for each of these words in pencil at least three different times in the textbook.

In my imagining her, I wasn’t thinking of writing about her or the textbook. I didn’t want to document my family’s immigrant experience. Instead, I aspired to be like the white American poets I admired, considering their stories as my own. I also didn’t want to write a clichéd immigrant story, to reminisce, to be a native informant, or to gain empathy and publications because of political circumstances. In a way, those iconic immigrant stories have become clichés, because their powerful and real narratives are constantly repeated. I didn’t know how to capture my experience and had no mentors or models for it. I still don’t know how this work can be done, but at least today there are many great immigrant poets from which we all can learn.

For the chapbook, I decided to use the structure and section titles of an ESL textbook. This framework allowed me to utilize different forms and provided a way to write about more personal and uncomfortable subjects. But the structure also determined the poetry. The result was a very different experience from my first chapbook, 99 Names of Exile (Newfound, 2019), which was formed around a group of poems that worked together. Writing poems that fit a structure means that I am less sure of the poems standing on their own. At one point, I also engaged the ESL book more closely. For example, a variation of the “Conversation Practice” took the form of an erasure of a page from the book.

Reflections on grandparents, food, and language are subjects in immigrant literature that can turn into clichés. All of them are also part of my chapbook. These topics tie immigrants to where they come from. Family, food, and language are often all we have left after everything is lost. Food becomes a source of pride for immigrants because it allows us to share our culture easily and accessibly. It can even change the adopted culture. When I decide to go out to eat, I don’t usually think salad or hamburger. I think, Indian, Mexican, Chinese, Italian? These different foods have become a part of the American society, the way that many other aspects of an immigrant’s heritage have not.

Food also plays an important role in Iranian-American culture. It is the only thing from Iran that my American-born cousins—who aren’t Muslim, don’t speak Persian, and have no interest in visiting Iran—know and share with others. I remember how in the past my family would send dried fenugreek leaves and barberries from Iran. You can now easily get all these Iranian items fresh in some metropolitan areas like Los Angeles County or via the internet.

Words—their sounds and shapes as well as their etymologies and histories—are another immigrant preoccupation. One of my surprising discoveries was my grandmother’s last name قریب (Qarib), which means close, near, or kin. This Arabic word in Persian is pronounced as Gharib if written into English. We don’t distinguish between the sound of Arabic ق (q) and غ (Gh) in Persian. They are pronounced as غ (Gh). So my grandmother’s last name, which was different from her children since women in Iran don’t take their husband’s last name, was transliterated as Gharib in English. We didn’t notice that Gharib (غریب), another Persian word from Arabic, means stranger, alien, or foreign. In one swift flight of linguistic destiny, my grandmother’s last name, like her, changed from what was near and kin to stranger and alien.

Kaveh Bassiri is an Iranian American writer and translator. He is the author of two chapbooks: 99 Names of Exile (Newfound, 2019), the winner of the Anzaldúa Poetry Prize, and Elementary English (Angina Press, 2021), winner of Rick Campbell Chapbook Prize. His poetry has been published in Best American Poetry 2020, Best New Poets 2020, Verse Daily, Virginia Quarterly Review, Copper Nickel, Beloit Poetry Journal, The Cincinnati Review, and Shenandoah. He is also the recipient of a 2019 translation fellowship from the National Endowment for the Arts. His translations have appeared in the Chicago Review, Denver Quarterly, The Common, Colorado Review, Los Angeles Review, Two Lines, and Massachusetts Review.

(To read more great poetry from Issue 17.2, you can buy copies of the issue in our online store, including the digital version, which is just $5.)