In our fall issue, we featured two poems by G.C. Waldrep, “The Healing Loom” and “The Arrythmias,” and we’re glad to host Waldrep’s reflection on how the latter poem came to life:

G.C. Waldrep: Everything comes from somewhere, but the process of building a poem—or being built by a poem—is one of the most mysterious processes I know. I know where the title of “The Arrhythmias” came from: my first middle-aged chest pain experience, in the fall of 2018 (after having sat through a particularly stressful committee meeting at my university). Two weeks later a poem arrived that was explicitly about that experience: “On Being Mistaken as Part of the Art at the Mattress Factory Museum in Pittsburgh” (now in The Earliest Witnesses). But two months after that, on December 23, 2018, “The Arrhythmias” arrived.

It’s a winter poem, an indoor poem. And much of it continues to mystify me. I vividly remember the first two phrases coming to me and wondering what to do with them. But when I review the poem, only bits and pieces correspond with anything we might call the shared world, the “real” world.

The terrible dreams in the deconsecrated chapel were real. Here’s the chapel. And I can date the dreams to the early hours of October 1, 2013, when I stayed there.

The theft of the peaches in childhood was real: my grandfather had handed me a basket of ripe fruit, intending I take them back to my aunt’s (where the rest of the family was gathered), but I reasoned that when he said “these are for you,” he meant me (I knew he didn’t, but language-lawyering runs in the family), so I hid behind my aunt’s house and ate them all.

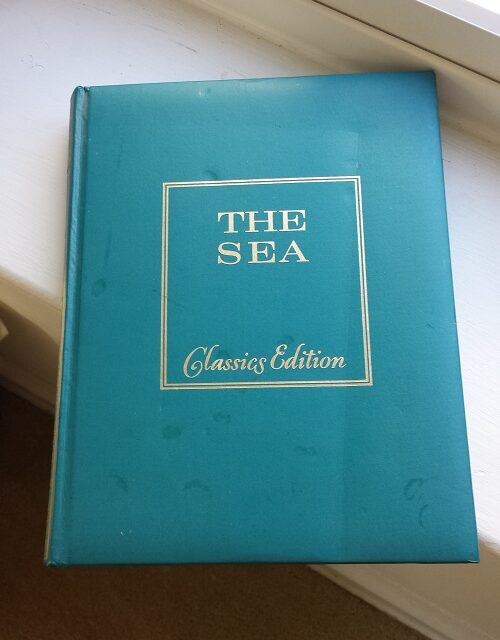

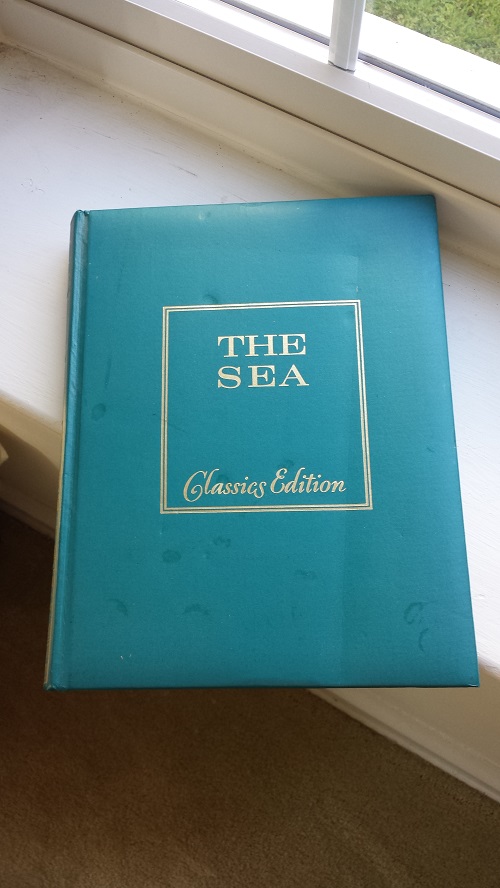

“The columbarium’s gravel promenade” is real, a flash memory from a bit of UK walking. But what is realest of these “real” elements is “the square, turquoise book entitled The Sea.” It, and my brief obsession with diatoms. It was a book I pored over for one or two years of my childhood—the images, before I could really understand the scientific writing. I hadn’t thought about that book (or diatoms) in decades, and then suddenly there it was again, surfacing in a poem. I had no idea where the book came from, or what had become of it.

A year later, in 2019, my parents informed me that they were cleaning out their house, and so the Permanent Museum of My Childhood was set to close. I would need to drive to North Carolina and empty my part of the attic, and I would need to do it now. It took me months to unpack the boxes once I’d brought them back to my house in Lewisburg, and . . . there it was, The Sea. Apparently at some point (presumably in 1986, when we sold my childhood home and moved to North Carolina), I’d filched it from our pre-move yard sale and packed it away.

So, the title; the chapel and the bad dreams; the filched peaches; a bit of graveled walk in a cemetery; and a book I’d loved when I was a child, when I was seven or eight. Those are the “real” bits. I was astonished as the poem unspooled, phrase by phrase revealing . . . something other than experience I could recall or pinpoint.

For me, part of the pleasure and shock of writing is precisely this unspooling, the known conjoined with the unknown. If I were a Freudian (or especially a Jungian), I could spend a great deal of time trying to “decode” the other gestures that make up the poem. And “decoding” is what readers often beg me to do: they think there’s a code, and that it, or I, am withholding information from them. They want that information.

I could say the poem is a kind of rippled reflection of my experience—all that glass—and I think that would be true. I could talk about the rivers and reservoirs of our blood—the sea of blood, if you will—washing through the organ we call the heart. I also see fragments and flashes of images that occur in other poems of mine. But I don’t think the poem is withholding information (and I know the poet isn’t). Visually and affectively the poem is composed of phrases, or shards. It arrived continuously (I have my original handwritten draft), more or less as it now stands. Allowing for those five exceptions, I don’t really know any more about the poem or its code than the reader does. I like to think about those other moments, the moments that seem to come from somewhere outside my personal experience.

What this all calls into question, for me, is the distinction between the “real” and the irreal, the shared and the sharable. Because what wasn’t “real” in any demonstrable sense is now very real: it comprises the poem, as a text artifact. And even if I can’t share with you the moment of the poem’s arrival, or the process by which it arrived (I know next to nothing about that), or its ultimate, denotative “meaning,” I can share the poem with you, shards and all, reflections and all.

I think good poems—good art—add to the stock of what is sharable and real. They are simultaneously gratuitous and enriching. They increase our sense of what’s in the world, what’s possible for a world, and, in inviting response, initiate us into that enriched, or enlarged, world. This is as true for me, as writer, as I hope it must be for any interested reader.

The only other thing I can offer you is the book itself, The Sea. I have it now on a shelf in my spare room. I keep wanting to pull it down and open it, re-experience whatever it was that drew me to it forty-six years ago. So far I’ve managed pulling it down, but not opening it. We’re sharing a house again, as we did when I was a child. It has waited a long time for me, and to appear in a poem. But that’s one thing books do well: they wait. I’ll wait, a little longer, with it.

G.C. Waldrep’s most recent books are The Earliest Witnesses (Tupelo/Carcanet, 2021) and feast gently (Tupelo, 2018), winner of the William Carlos Williams Award from the Poetry Society of America. Waldrep lives in Lewisburg, Pennsylvania, where he teaches at Bucknell University.