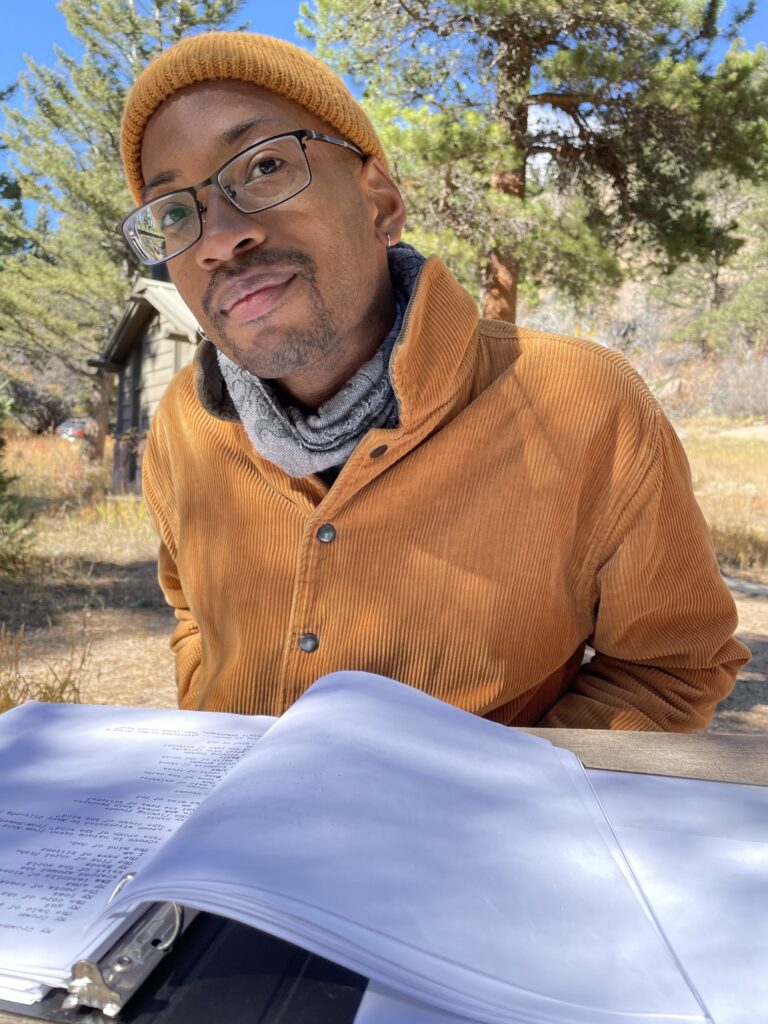

From Our Contributors: Rethinking The Urban Pastoral, by Malik Thompson

4 Minutes Read Time

Assistant Managing Editor Bess Winter: Malik Thompson’s poems in Issue 21.1, “Valkyrie” and “Haibun,” zero in on natural phenomena that happen where urban meets nature: a poem narrated from the perspective of a honeybee, moss scraped off a gravestone. Here, Malik expands, in words and photos, on how they bring nature into work that’s rooted in an urban setting.

Rethinking The Urban Pastoral

“Historically, pastoral has been a literary genre… celebrating the idealized pleasures and joys of country life… The pastoral is by definition the product of city-dwellers, looking back at a life they have never led…”

Reginald Shepherd, “Toward An Urban Pastoral”

Found in his 2007 essay collection Orpheus in the Bronx, Reginald Shepherd’s essay, “Toward An Urban Pastoral,” shifted my thinking in regard to the use of “nature” imagery in contemporary American poetry. In brief, Shepherd argues that poets must strive to create a more robust lexicon for rendering life in the city.

Encountering Shepherd’s essay as a younger poet, I recall being eager to wrestle with the unspoken challenge asserted by this sharp, studied elder. How do I write the city? is a question I carried into the crafting of my earliest poems. This question quieted as time passed, making way for me to write unencumbered by Shepherd’s acerbic intellect.

The two poems chosen for publication in Issue 21.1 of The Cincinnati Review are the product of a maturation of voice that began in 2018.

Having moved back to Washington, DC, the city I’m from, in 2017, my poems became inundated with flowers, birds, and other images that can be considered “nature” imagery. While the presence of these elements may seem antithetical to Shepherd’s urban pastoral, anyone familiar with the topography of DC would know that, in spite of being a metropolis, each of the city’s quadrants is lush with plant and animal life.

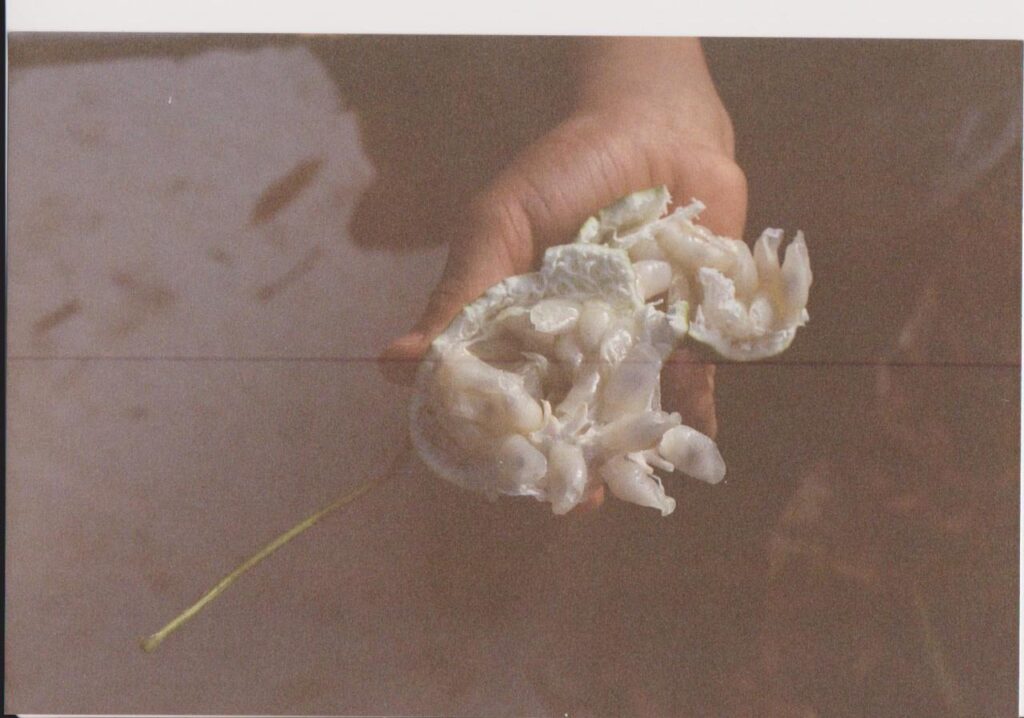

Image, Left: An aloe plant sat before a window overlooking changing leaves in Northwest DC.

Beyond wildlife considered typical of urban areas, such as pigeons and squirrels, there were deer, blue jays, cardinals, and raccoons to be witnessed on any given day. My earliest memories include purple summer evenings dense with clouds of fireflies, their population now severely diminished. In elementary school, we picked buttercups and thrust them beneath the chins of other children, a “green” chin a sure sign of a crush. Honeysuckle grew wild in most places; the sheer quantity of flowers made it so we felt no guilt when breaking them apart for a single drop of heavily scented nectar. These encounters with the plant and animal world—and many others—all took place within a city’s boundaries.

Still, other poems I write incorporate buses and cars, the subway train, and the facades of buildings. I admit, I find it difficult to render the modern human world in my poems. What the word “train” evokes in the mind of a reader can never be as layered and stimulating as the word “flower.” I find inspiration in the works of poets such as Audre Lorde, Adrienne Rich, and Muriel Rukeyser: poets who wrote the city to a standard I strive to meet.

Having metabolized Shepherd’s ideas without cross-referencing them against my own experiences, I’d annexed a major facet of my lived experience from my poems by uncritically following someone’s else’s rubric. I don’t mean to imply that Shepherd is necessarily incorrect; I simply hadn’t thought about the reality that many cities trouble the divide between “nature” and “urban,” and that I’d grown up in one.

As poets continue to expand our lexicon for rendering the city, I hope that any given city’s relationship to the nonhuman world is written with a specific and intimate knowledge. Shepherd wrote Chicago. Lorde, Rich, and Rukeyser all wrote New York City. And my chosen project is to write Washington, DC.

Malik Thompson (he/they) is a Black queer person from Washington, DC. His work has been published in Diode, Denver Quarterly, Poet Lore, and elsewhere. He has received fellowships and residencies from organizations including Cave Canem, Lambda Literary, the Anderson Center and Sundress Publications. He can be found on Instagram via the handle @latesummerstar.