From Our Contributors: Hadley Moore On Iconic Images of Our Assassinated Political Heroes

5 Minutes Read Time

[wp-reading-progress-ert]

Assistant Managing Editor Bess Winter: Hadley Moore’s story in issue 21.1, “Wait It Out,” deals with its protagonist’s relationship (or non-relationship) to the tumultuous history of the 1960s, specifically the assassinations of political figures. We promise we didn’t plan for the story’s themes to resonate so directly with current events here in the U.S., but, nonetheless, this seems like a good time to take a closer look at America’s relationship to its martyrs through the iconic photos that still define them. Please note that some of these photos can be disturbing, and depict the aftermath of violence.

From Hadley:

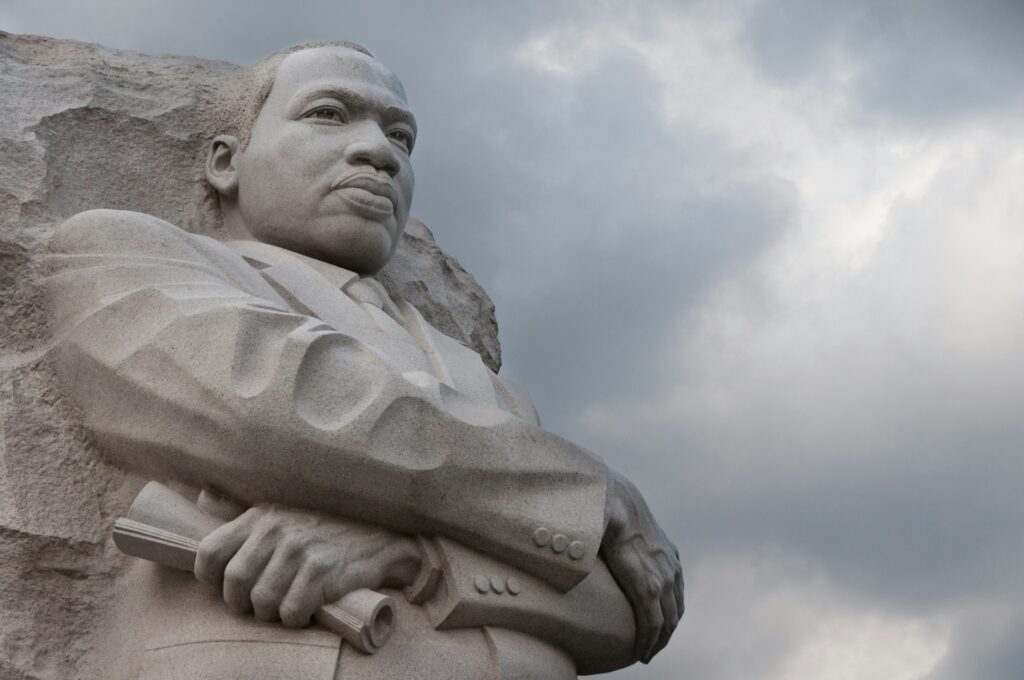

My story “Wait It Out” is part of a manuscript I’ve been describing as a collection of short fiction focused on characters who have a fascination with, or perceive some connection to, the assassinations of the 1960s, primarily those of John F. Kennedy, Malcolm X, Martin Luther King, Jr., and Robert F. Kennedy. When I began work on it I did a lot of image searches, at first mainly reminding myself of famous photos: JFK in the convertible, Malcolm X on the ballroom stage, MLK on the motel balcony, RFK in the hotel kitchen.

References to many of the photos I spent early-morning hours scrolling through started finding their way into the text. The first page of “Wait It Out” has my narrator saying, “I met the busboy who was there when Bobby Kennedy was shot. You know that photo? The kid in the kitchen? The white jacket?” (She didn’t ever meet him. She’s attempting to get a rise out of her reticent nephew by telling him one of what she calls her “crazy stories.”)

Part of me is tempted to dismiss my being drawn to the photos. I’m not much of a visual thinker, not an artist; I have no particular interest in photography. What’s more, there were no doubt times I scrolled photos as a stall tactic. Stuck with the words, I could always just look at pictures and tell myself I was still working on the manuscript.

But I do think it’s more than that. All those photos—the great volume of them, portraits and snapshots, official and candid—show these four men as so very human; that is, they were only human. That is, no one is coming to save us. We have only ourselves, only humans and more humans. This is one big reason I find the assassination conspiracy theories so uncompelling (see Max Boot on the JFK theories, for example): these four were as destructible as any of us, as flesh-bound, as mortal. “Small” people can indeed hurt “big” ones. You’d think they should be more protected somehow—and I’m not talking about security details or the Secret Service—but they were as vulnerable as the rest of us.

I am older now than any of them ever were. But they still seem older-er to me, more serious, more adult. Maybe it’s the suits. The old-timey hats? Even just the black and white. It’s also the frozenness in time.

In my early image searches I came across various photo illustrations, some with serious intent, whether artistic or documentary, but there were also a lot of Photoshop hack jobs: imagined age progressions and the like. Also wildly ahistorical depictions of all of them together, as four great buddies, the Super Friends of the 1960s—as though to elide what might make us feel discomfort or disappointment in any one of them (see again: humanity and its vulnerability, its imperfections). Actual photos of them together can be piercingly sad, though: MLK and Malcolm X; the newly widowed Coretta Scott King with RFK and his wife, Ethel—Bobby would be dead, too, within two months.

My parents were only teenagers when JFK was killed; I was born almost exactly nine years after RFK died. I can’t entirely account for my fascination with this season of assassinations, which well predates me. But my interest is real and it’s persistent, and now it’s finding some outlet in my fiction.

My characters’ fascinations are distinct from mine and from one another’s, provoked and fed by varied circumstances. “Wait It Out” begins with the line, “My nephew is writing a book, he says, about Martin Luther King, Jr.” Late in the story this narrator imagines addressing her dead husband, Adam: “Would you tell [our nephew] where you were? When MLK was killed, Adam? JFK?”… And where you were when I died, Adam, if I had been the luckier?” Still later she thinks to herself, “When Adam died, I was there” [emphasis added here].

Our tendency to tell these where I was stories, of so-called “flashbulb” moments, is illustrative, I’d say, of the very human need to locate our selves and our stories in the context of larger ones. And when we weren’t there, couldn’t possibly have been, maybe even weren’t yet anywhere—well, then, sometimes we just look at the pictures.

Hadley Moore’s collection Not Dead Yet and Other Stories (2019) won Autumn House Press’s fiction contest and received many other commendations, including being longlisted for the 2020 PEN/Robert W. Bingham Prize for Debut Short Story Collection. She is an alum of the MFA Program for Writers at Warren Wilson College.