7 minutes read time

Assistant Managing Editor Bess Winter: Nikki Barnhart’s “Rabbit, Rabbit” plays with time, loneliness, and loss, all viewed through the prism of one who is surrounded by artifacts of her past—or, as is the case with many of the rabbits in the art Nikki explores with us today, perhaps she’s trapped by them.

Down the Rabbit Hole—Strange Rabbits in Art

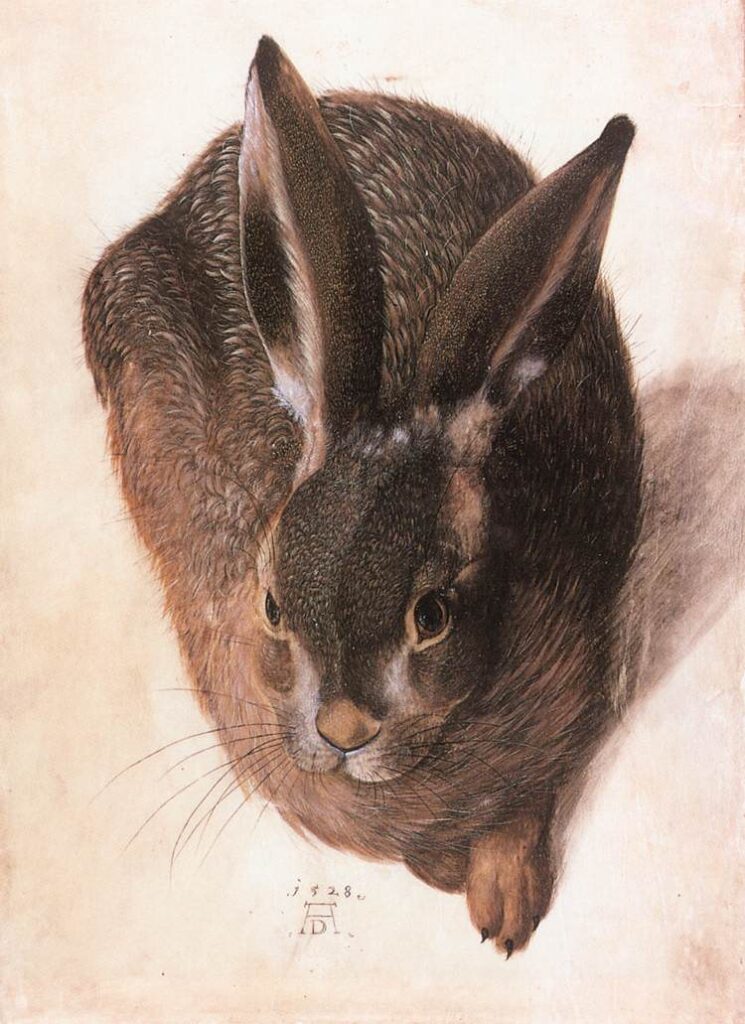

At the center of “Rabbit, Rabbit,” my short story in CR 21.1, is Albrecht Dürer’s Young Hare, a print of which hangs in the childhood home of the story’s narrator, a place teeming with centuries of history, a bunch of unwound clocks, tiny doors that open to nowhere—and possibly, rabbits trapped in the walls, or ghosts of a past that is never quite past, especially not so deep in the country where time seems to stand still: “In the living room, next to the grandfather clock, there was a painting of a rabbit. It was very simple, but also very lifelike. And very famous, as her mother told her when she was a child. Her mother showed her that in the rabbit’s eyes, you could see the reflection of the window panes of the artist’s studio, the escape to the outside world the rabbit would never make it to. Instead, it remained locked forever inside the painting.”

Albrecht Dürer

Young Hare, 1502

Source: WikiArt

It was this theory that the eponymous hare was a live model that Dürer captured and held hostage in the name of art, this undeniable detail of a windowpane’s reflection visible in its eyes, whether or not that theory is true, that led me to a fascination with the painting and sparked “Rabbit, Rabbit,” a story that explores the many mythologies attached to rabbits and hares: symbols of fertility and luck, innocence and rebirth—but also, madness and doom. It also led me down what I can only accurately describe as a rabbit-hole into exploring other captivating—and eerily haunting—depictions of rabbits in art, beginning with a lineage inspired by Dürer.

Hans Hoffmann

Hase, or A Lying Hare, as Seen From the Front, circa 1580–1585

Source: Web Gallery of Art

Dürer was an artist associated with the German Renaissance, but he also inspired a Renaissance of his own. Hans Hoffmann (not to be confused with a 19th–20th century artist of almost the same name) was perhaps the most zealous member of the “Dürer Renaissance,” being that he went as far to use Dürer’s monogram of “AD” to sign one of his own paintings of a hare that, at first glance, looks like it could be Dürer revisiting his own Young Hare from a different vantage point.

Hans Hoffmann

A Hare in the Forest, circa 1585

Source: Getty Museum

But it’s Hoffmann’s A Hare in the Forest (After Dürer) (where he fully cops to his inspiration) that I found myself most intrigued with. This hare’s lush and almost mythical backdrop is a stark contrast to the void surrounding Young Hare. It feels like the kind of background that might be found behind an image of a unicorn in art around the same period—another symbol for innocence and purity—or other such magical creature. Perhaps this surreal quality has something to do with the fact that the flora surrounding the hare could never actually co-exist in reality, placing the painting firmly in a dreamworld of imagination, despite its naturalistic environment.

Researching Hans Hoffmann led to me to Flemish artist Joris Hoefnagel, and his own probable “Young Hare” rip-off: a scene from his manuscript The Four Elements that depicts a Dürer-esque (but with a decidedly Hoefnagel flourish) hare sitting across from a rabbit, displaying the differences between the two species—with a mythical jackalope hanging out between the two.

Joris Hoefnagel

Plate 47, circa 1575-1580

Source: National Gallery of Art

Sir John Tenniel

Illustrations from Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, circa 1865

Source: Project Gutenberg

I’ve been bewitched by John Tenniel’s Alice illustrations ever since I was a child. They appear almost realist in their careful detail, but the scenes they depict are wildly bizarre, taking cues from the grotesque.

It may not be too much of a stretch to say that Tenniel’s painstaking attention to detail may have been inspired by Dürer’s work—a link is found between them in Tenniel’s The Knight and His Companion, an illustration for the satirical magazine Punch, that borrows the imagery of Dürer’s Knight, Death and the Devil.

Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland contains both a rabbit and a hare: the perpetually tardy White Rabbit, and the mad March Hare. As you may have guessed, the narrator’s name in “Rabbit Rabbit” alludes to this second figure.

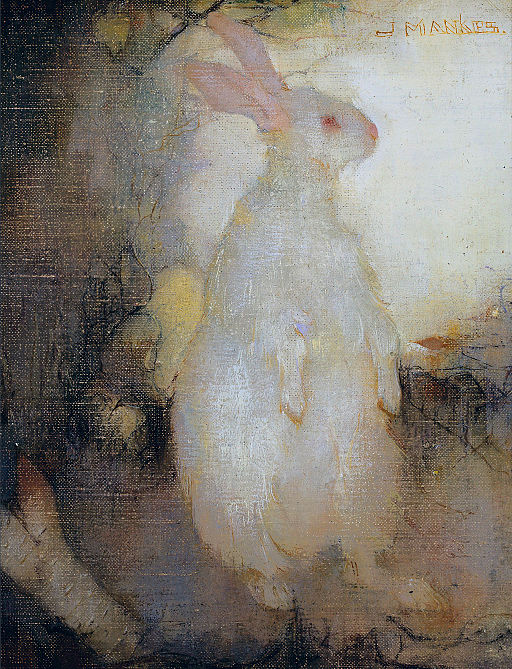

I find this piece by Dutch artist Jan Mankes especially eerie for the upright, human-like posture the rabbit is assuming, appearing to possess an agency Dürer’s hare can only long for. I wonder if this might be a reference, even slightly, to Carroll and Tenniel’s white rabbit.

While rabbits can, in fact, stand on their hind legs, it is Mankes’s dream-like treatment of this subject—its soft haziness quite a diversion from Dürer’s sharp specificity—that makes it appear more than a little otherworldly.

Jan Mankes

White Rabbit, Standing, 1910

Source: Sotheby’s

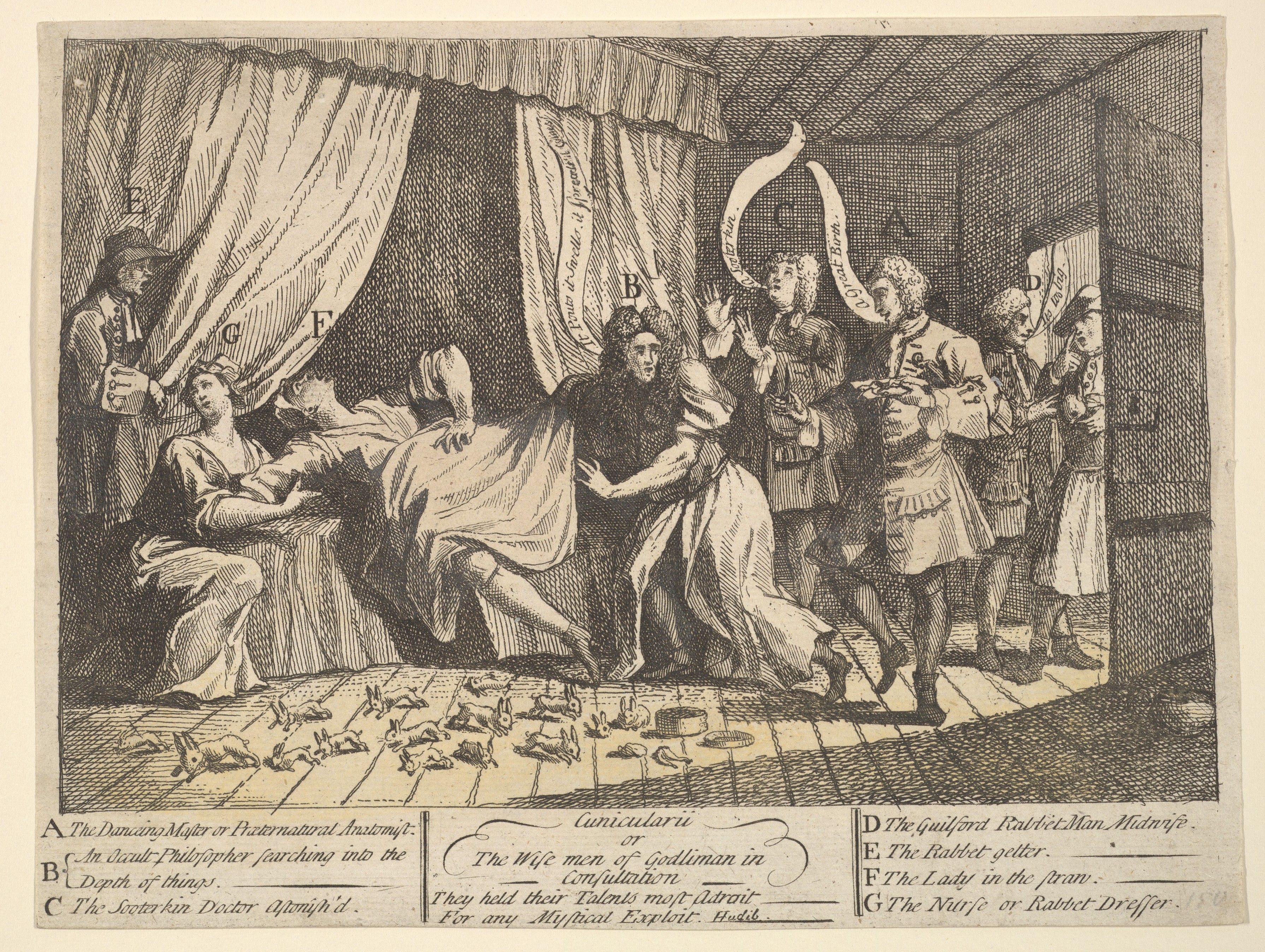

William Hogarth

Cunicularii, or The Wise Men of Godliman in Consultation, 1726

Source: The Metropolitan Museum of Art

In “Rabbit, Rabbit” an ultrasound tech compares the size of the narrator’s unborn child to a baby rabbit. But there’s an absolutely wild real-life case in which an 18th-century woman named Mary Toft tricked the public (for a while!) into believing she actually gave birth to rabbits, claiming that she had seen a pair of rabbits in the wild that had eluded her, and she had subsequently been overcome with an insatiable craving for rabbit meat.

The truth is perhaps even stranger than fiction: Toft had placed dead rabbits into herself to simulate the “births.” The illustrations depicting the hoax by satirist William Hogarth are appropriately outlandish, portraying the rabbits as alive instead of stillborn, and simply must be included among this list.

Andrew Fitzwilliam Tait

Rabbits on a Log, 1897

Source: Metropolitan Museum of Art

I’m struck by this seemingly ordinary painting for a few reasons. One being that the spiritual resemblance these rabbits seem to bear to Dürer’s hare—they feel somehow indebted to its legacy. And for the very human-like gaze the rabbit on top of the log casts over the rest of the scene, something in his eyes different from the two resting on the ground. It is this type of gaze that I think March feels on her at the end of “Rabbit, Rabbit.”

Wilhelm Kühne

Optogram, 1878

Source: The College of Optometrists

It’s not exactly art but certainly a striking, chilling image on its own right, and one that ties uncannily back to that mirrored reflection in the Dürer hare’s eye.

In “Rabbit, Rabbit,” the narrator recalls the sacrifices of the “rabbit test,” an archaic pregnancy test method that involved inserting woman’s urine into rabbits, who would then be killed and dissected to see if their ovaries had enlarged—if so, the woman was pregnant. Optograms are another way that rabbits have served as nonconsenting sacrifices for science.

In the late 1800s, a physiologist named Wilhelm Kühne experimented on animals to derive images from a retina to be used in forensics research (with the idea that if we could capture that last image on the retina before death, it would be possible to determine the identity of murderers). Kühne’s most notorious experiment, creating the image to the left, was on an albino rabbit, with its head fastened to a barred window.

The result is the rabbit’s last glimpse at the world before death, that longing for escape in the Dürer hare’s eyes forever immortalized; if we could get inside Young Hare, this is what we might see.

Nikki Barnhart’s work has appeared in The Cincinnati Review, Post Road, Juked, The Rumpus, Superstition Review, Phoebe, and elsewhere, and has been nominated for a Pushcart Prize, Best of the Net, Best Small Fictions, and the AWP Intro Prize.