3 minutes reading time

Assistant Managing Editor Bess Winter: As North Americans, when we think about current-day Crimea, our first, and perhaps only, association may be with war. In her haunting essay in Issue 21.1, “Gone Are the Blackberries, the Alycha, the Asters, and the Rusty Spigot,” Yekaterina Droog pays tribute to her grandfather’s lost garden and the Crimea of her youth. Today Yekaterina graciously offers us a further glimpse of the area as we join her on this tour of some of her favorite spots.

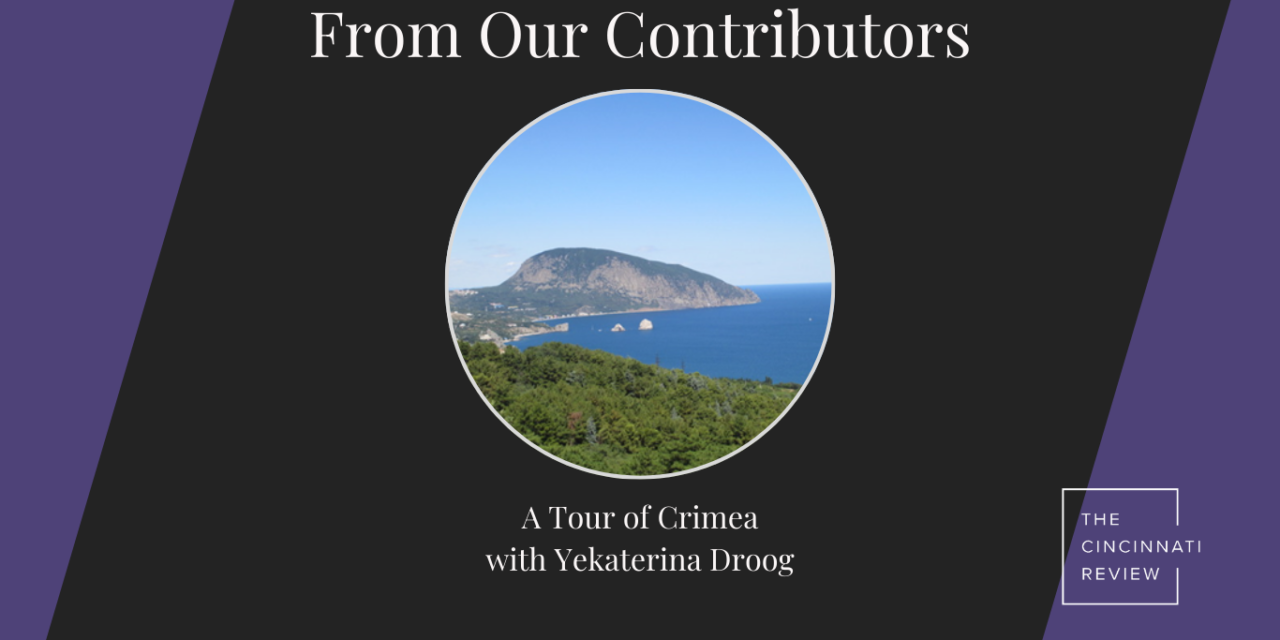

A Tour of Crimea with Yekaterina Droog

What started as a loving tribute to my grandfather has turned into a love song for my land. In the 1990s, when I first came to the United States, very few people knew of either Crimea or Ukraine. My meant-to-be-helpful hints about the 1945 Yalta Conference did not always work. To avoid blank stares and silences, I started saying that I was from Russia. Everybody knew “Russia.” Everybody still knows “Russia.” “Russia” is just two-syllables long, much faster to enunciate than the five syllables of “the Soviet Union.” Since the Soviet Union had already ceased to exist, “Russia” became my convenient go-to.

Due to Putin’s annexation of Crimea and the beginning of the war in Ukraine, many Americans have become aware of both Ukraine and Crimea, even if they still struggle with the concept that one can be simultaneously a Russian and from Ukraine. Yet, their awareness of Crimea is often framed by the images that offer only one story, the story of the military conflict—explosions on the bridge near Kerch, armored vehicles, soldiers in fatigues, warships prowling the Black Sea, drones. I am hoping that my essay and a few of the pictures from my last trip to Crimea would help augment this notion of the peninsula and reveal it as the subtropical, historical, and multicultural jewel it truly is.

History

The city of Sudak has outlived multiple empires—the Roman, the Byzantine, the Ottoman, and the Russian. It used to be one of the stops along the Silk Road; it survived the dominion of the Mongol Golden Horde; and it was fortified by the Genoese merchants in the fourteenth century.

Culture

In the language of the Crimean Tatars, Ayu-Dag means “Bear Mountain.” According to the Tatar legend, once upon a time, a bear adopted an orphaned girl. When his human daughter grew up, she met a young man who got shipwrecked nearby. The young woman fell in love and decided to elope with the sailor. Heartbroken, the bear lay down by the seashore and started siphoning the water, hoping to draw the sailor’s boat and the girl back. He failed, but the salt in the water turned him into a rocky mountain, a monument to the bear’s longing for his lost child.

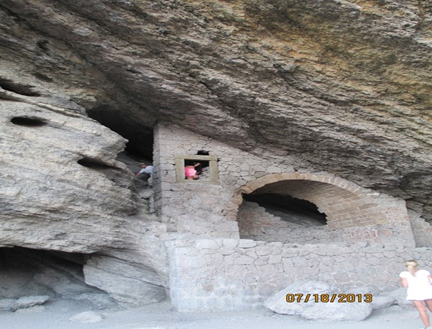

Tsar’s Vineyards and Shalyapin’s Grotto

In the 1870s, Russian Prince Lev Golitsyn established a winery in Noviy Svet, where he was hoping to produce a world-class sparkling wine. Having achieved his goal, he eventually bequeathed his wine-making empire to Tsar Nicholas II. Golitsyn’s spectacular wines were stored in the natural caves by the sea. A famous Russian bass singer Fyodor Shalyapin once performed in the grotto below.

Subtropical Beauty

From the ascetic beauty of the Crimean mountains that shield the southern coast of the peninsula from the harsh northern winds to the Mediterranean flora and fauna near the beaches, Crimea is a treasure all year round.

Yekaterina Droog grew up in Crimea, Ukraine. When she was nineteen, she moved to the United States. She has been teaching writing and literature in the US public school system for the past twenty-five years. During school vacations and on weekends, she writes fiction, nonfiction, poetry, and professional essays.