By now followers of our blog have been privy to posts by our new sunny-on-the-surface-yet-with-dark-hidden-depths staffers Becky Adnot-Haynes and Lisa Ampleman (by day, they read submissions; by night, they prowl the city, scrawling HYPERCORRECTION MUST DIE in scarlet lipstick on the windows of citizenry who have been heard to say, in the course of a casual conversation, the maddeningly WRONG phrase “between you and I”).

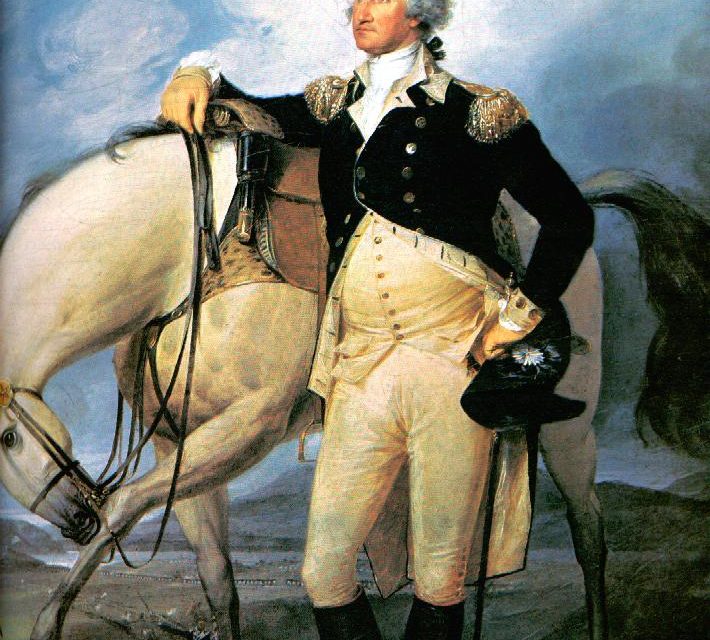

Our other new staff member, Matt O’Keefe, is a crusader of a different stripe. Often we’ll catch him muttering under his breath about his hero George Washington, how pres numero uno is underappreciated, the poster child for poor dental hygiene, unfairly pictured with dinghys or cherry saplings when he’s about SO MUCH MORE. “Why are people always going on and on about la-dee-dah Jefferson,” Matt will complain while making the mindlessly-yapping-mouth gesture with his hand, “when Washington was totally the bomb dot com!” We have to keep him from inserting facts about GW into the manuscripts he edits, or grading down submissions for not mentioning the Great Man. But here at CR, we accept that people are not perfect, and we try to accommodate each other’s harmless little foibles. When Matt said he wanted to write something for the blog, we knew what was coming, but he did single-handedly engineer our new online submissions program, so we were willing to cut him some slack.

Matt O’Keefe: Last weekend I went with my family and some friends to Gorman Heritage Farm just north o f town to rustle some hay and maybe eat a cinnamon donut. While there we watched a man shovel manure balls into a wheelbarrow while the horse who made the balls looked on. It was a glistening chestnut animal with a long, noble head, of which I remarked to my friend, “Imagine waking up with that in your bed.” But guess what, it wasn’t a horse; it was a mule. I never knew a mule could be so beautiful. The guy with the shovel told me that George Washington first brought mules to North America and improved them with his meticulous experimental breeding. A mule is a combination of a female horse and a male donkey; if you reverse the genders, what you get is called a hinny. Famously, both mules and hinnies, having a number of chromosomes (63) indivisible by 2, cannot reproduce with other mules and/or hinnies, though sometimes a male horse or donkey will make a female mule or hinny pregnant.

f town to rustle some hay and maybe eat a cinnamon donut. While there we watched a man shovel manure balls into a wheelbarrow while the horse who made the balls looked on. It was a glistening chestnut animal with a long, noble head, of which I remarked to my friend, “Imagine waking up with that in your bed.” But guess what, it wasn’t a horse; it was a mule. I never knew a mule could be so beautiful. The guy with the shovel told me that George Washington first brought mules to North America and improved them with his meticulous experimental breeding. A mule is a combination of a female horse and a male donkey; if you reverse the genders, what you get is called a hinny. Famously, both mules and hinnies, having a number of chromosomes (63) indivisible by 2, cannot reproduce with other mules and/or hinnies, though sometimes a male horse or donkey will make a female mule or hinny pregnant.

All this is to say that horses, not mules or hinnies, feature prominently in the current issue’s poems by the below-listed contributors. And, no, that’s not a typo, Ben Debus’s poem is not actually titled “The Abandoned Horse at 824 Sleepy Hollow Road.” I won’t give away the equine angle except to say it has something to do with the metaphor he mentions.

Lavonne J. Adams: I have been fascinated for years with matters of depth perception, as if I were a painter and everything around me part of a still life. On the particular Saturday when I wrote “A Certain Perspective,” the Preakness was about to begin. The announcer’s small talk about the track caught my ear, especially the words “optical illusion.” The scene at the track and my own physical reality began to merge. But I was completely surprised by the poem’s last line, which I think is always a pleasure for a writer—that acknowledgment that the subconscious has its own agenda, and sometimes we must allow it to set the pace.

F. Daniel Rzicznek: I wrote “Horses” in the span of an afternoon, the images flying one after another onto the page. I see this poem as both a tribute to the beasts that have labored for thousands of years to build our civilizations and as a warning that the universe eventually swallows all. As Americans, our history surrounds us, and one of the things I’ve been interested in lately is giving a voice to landscape itself and inventing memories for the earth. I tried to allow history to shade certain parts of the poem as well. How often we forget that our lives are built on loss.

Ben Debus: “The Abandoned House at 824 Sleepy Hollow Road” is one of a group about abandoned houses. In part, it has to do with a concern about the foreclosure crisis. It makes me wonder where the people who leave their houses go; and (as in this one) what happens to a house untended, unlived in. This one burns. The ways that a house can fall apart are astounding. That we put so much into houses, our things, time, hopes: The metaphor is, in one way at least, an attempt to express the aliveness we grant to houses.