When Cincinnati Review staff member Don Peteroy isn’t busy reading for class, writing 200-page translations (via Google Translate) of 16th-century German adaptations of Hamlet, or playing in his band, he likes to ask writers he admires irrelevant questions. We’re honored to have two replies to share with you, from Lauren Groff and David Yost.

Lauren Groff is the author, most recently, of the novel Arcadia (Voice, 2012), as well as of The Monsters of Templeton (Voice, 2008) and the story collection Delicate Edible Birds (Voice, 2009). Her short stories  have appeared in many journals, including the The New Yorker, Atlantic Monthly, Ploughshares, and Glimmer Train, as well as in the Best American Short Stories in 2007 and 2010. She lives in Gainesville, Florida.

have appeared in many journals, including the The New Yorker, Atlantic Monthly, Ploughshares, and Glimmer Train, as well as in the Best American Short Stories in 2007 and 2010. She lives in Gainesville, Florida.

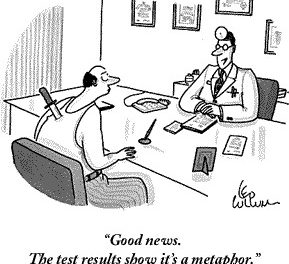

Question: Where are your shoes? I’m not talking about your literal shoes, but your metaphorical ones.

LG: To understand where exactly my shoes are—which is a very good question for me, in truth, because I prefer to go barefoot at all times, splinters be damned—I need to first understand what my shoes are. Is it strange that I thought at first of the less-common genre of shoe? Not the kind that lovingly cups tender toes and protects those sad and fallen arches from shattered glass; not my authentic cowboy boots, bought in a flush of glee when I found out I’d won a fellowship I was longing for; not the soccer cleats, a whole size too small, to which I’d sacrificed many blackened toenails, but which were the only shoes ever to allow me to score. No; I thought of a rusted horseshoe above a barn door at a farm in Quakertown, Pennsylvania, where my family lived for a few years before returning to Cooperstown for good. The horseshoe door led to the paddock, where our tiny pony, Imp, lived. Imp was a nasty bastard. Once, when I was five years old, I was contentedly riding on Imp’s back when the jerk tore out of my father’s grasp, rushing me headlong toward a fence, an oak, an apple orchard; I narrowly escaped brain damage by clinging to his mane with my fists and teeth like a flapping human limpet. His horseshoe had been nailed up above the door—for good luck, I was told. On the day I noticed that one nail had come loose, canting the horseshoe down and spilling some of its luck, I found our poor white cat, Marshmallow, in a trough inside the barn. He was stiff and, it finally dawned on me, dead. For a long time afterward, I stood in the doorway, under the horseshoe, unable to go in or out. Inside, all was dark, humid, stinking, a trash-bin full of dog food crawling with maggots, the beloved cat who wouldn’t stir. Outside was an angry pony, ready to spill my brains. Inside, safety but obscurity; outside, risk and sun. We are born with a certain amount of luck, and the rest we have to make for ourselves. I took a step, choosing the light, the flight in the face of the demonic. That’s where my horseshoe still swings, half full of luck, half ready to be filled.

A former Peace Corps Volunteer, David Yost has served on development projects in the United States, Mali, and  Thailand. His fiction has appeared in more than twenty publications, including Southern Review, Witness, Pleiades, Asia Literary Review, and The Sun. His anthology Dispatches from the Classroom: Graduate Students on Creative Writing Pedagogy is forthcoming in November 2011 from Continuum, and his story “The Carousel Thief” will appear in our next issue, due out in May. An appreciation of that story—written by Luke Geddes—appeared on our blog earlier this week.

Thailand. His fiction has appeared in more than twenty publications, including Southern Review, Witness, Pleiades, Asia Literary Review, and The Sun. His anthology Dispatches from the Classroom: Graduate Students on Creative Writing Pedagogy is forthcoming in November 2011 from Continuum, and his story “The Carousel Thief” will appear in our next issue, due out in May. An appreciation of that story—written by Luke Geddes—appeared on our blog earlier this week.

Question: Let’s say that an angry God has put a curse on you. The God says, “Every time you write a new story, poem, play, or essay, a Shakespeare play will vanish from both history and collective memory.” Would you continue to write stories?

DY: Do I get to pick? A world in which nobody reads Pericles, King John, Cymbeline, The Two Noble Kinsmen, Henry VIII, and the three plays of Henry VI would be basically the same as ours, so that buys me eight more stories at least. I imagine I’d draw the line at Coriolanus and The Merry Wives of Windsor and then try to break into television.