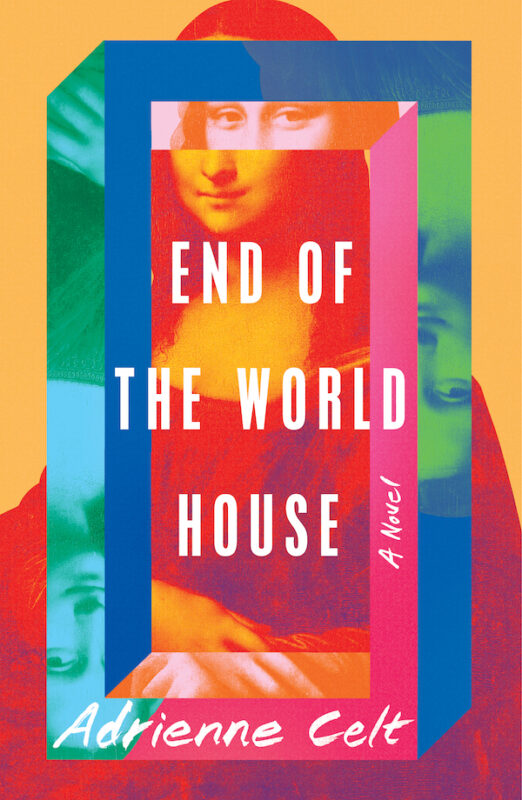

Associate Editor Lily Davenport: Adrienne Celt’s most recent novel, End of the World House (2022), traces the intricacies of a friendship in the process of collapse, within the frameworks of a slow-burn apocalypse and an existentially fraught time loop. I loved the book’s commitment to exploring the intense, and often messy or unflattering, feelings caught up in the demise of a long-term friendship; in a kind of magic trick, its structural interest in repetition and stuck-ness underscores that emotionality without ever making the reader feel trapped or bogged down. Adrienne generously agreed to answer some questions about End of the World House, productive repetition, and writing embodied narration for us, and I’m very happy to present the fruits of our email conversation below.

Adrienne will be on the UC campus this week—along with her agent, Emma Patterson of Brandt and Hochman!—as part of our English Department’s Visiting Writers series. If you’re in town, be sure to stop by her reading on Thursday, 2/27, at 5:30 p.m., and the conversation featuring her and Emma Patterson on the writer/agent relationship on Friday, 2/28, at 3:30 p.m. (both events to be held in the Elliston Poetry Room at UC’s Langsam Library). We hope to see you there!

One thing I was immediately drawn to in your third novel, End of the World House, was the acerbic, competitive element of Bertie and Kate’s friendship—and, most delightfully, the fact that, while Bertie is certainly displeased on the numerous occasions when Kate looks hotter or better-dressed than she does, they’re not really competing over a man. (Certainly, men and their attentions intrude on their friendship, which is perennially distressing to Bertie, but that’s a separate problem.) Rivalry also appears on a fundamental thematic and structural level: the novel’s many timelines/iterations/parallel universes materially compete for Bertie’s attention, and even her basic sense of identity and selfhood. And you’ve written elsewhere about the function that creative and professional rivalry has served in your own life—both as a motivator and as a distraction—and about the weird hollowness of losing a creative nemesis. Could you tell us a bit about your approach to rivalry as a kind of craft technique? And what is your broader creative and personal relationship with competition like, these days?

I try not to let things like rivalry enter into my writing process too much, because that would center thinking that exists outside the world of the book. When I’m writing a first draft in particular, I want to stay in the book’s world, its flavors and textures and sense of myth. That said, I do think spite is an excellent motivating force (rarely against other writers, but just . . . ambient spite), so I guess it follows me into my process in that way. Anything you can do to get the work done, right?

Beyond that, the way rivalry plays out in a book like End of the World House depends entirely on how it plays out in the lives of the characters: I didn’t chose rivalry as a quality to give to Bertie and Kate just to process my own issues, I chose it because it was appropriate to them and how they relate to one another, what the push and pull of love is like in their lives as I was exploring them. Those kind of character dynamics are definitely inflected with my personal experience (more so in End than elsewhere in fact), but since I’m not writing memoir, my life is a more of a well to draw from than a series of prescriptions.

Something else I really admired about End of the World House was the very necessary repetition of both scene structures and physical spaces. You get so much mileage out of Bertie and Kate’s hotel room, for instance—or from repeated objects, like the multicolored bathrobes—but it never feels stale. I’d love to hear more about your approach to composing, and then to revising, some of those scenes; how did you navigate the challenges of constructing a narrative that is iterative and cyclical, but never stagnates or becomes rote? (Optional, but: I’m also curious to hear if this has any relationship to your experience working in a four-panel form for Love Among the Lampreys; even in a completely different form, you seem committed to using external, structural constraints as an anchor and as a tension-building strategy.)

Thank you so much for saying that! I had a lot of fun and a lot of angst related to that part of the process, because I wanted the repeated scenes to be both obvious as repetitions, and yet to still move the story and the character dynamics forward. So it was occasionally a struggle to decide how much to include, where to focus, in order not to bog the book down. (Sometimes I will admit that I felt like I was the one trapped in the Louvre.)

A guiding principle for me, when I’m stuck in this kind of creative conundrum, is to go back to character, and back to the body. So if, for instance, I was trying to figure out how to evoke the milky space between Kate being there and not being there, it made sense to look at Bertie’s physical and mental state as guidance for the scene. Make her angry! Make her drunk! Let the drunken, angry awareness guide what she was seeing and feeling, even in the familiar space of their hotel room. That gave me something very tactile and relatable to construct: a scene where Bertie feels seasick in bed because she drank too much, and can’t remember if or why she’s mad at Kate when they both wake up in the room together. A familiar rationale (over-indulgence) to layer on top of an unfamiliar situation (time loop!). No matter how weird the world was being, the characters were still physically alive and present in ordinary ways.

One of Bertie’s central problems is that she uses insulation to cope with isolation. It’s not that she’s purely materialistic, but she does take a lot of pleasure and emotional consolation from the lifestyle that her unusually-well-paid-for-an-artist job permits, especially as a contrast to the grief she’s still processing after the loss of her parents, and the emotional distance that’s come to divide her from Kate; I felt like I got just as much detail about the creature comforts she takes solace in, as I did about the ongoing apocalypse. She’s also insulated emotionally, albeit in a less pleasant way, by the sheer repetitiousness of her work: the dinosaur mascot she draws over and over again in endless variations that echo her timelines’ multiplicity. Could you speak further to that insulation/isolation tension?

That’s a great observation. I don’t know that I framed it for myself, in the world of Bertie’s job, as insulation so much as willful blindness, wherein she let herself ignore certain unpalatable facts about her company and the tech world generally in order to keep a grip on her comfortable existence. But you’re also right, she’s doing so within the framework of not having much else to hold onto. The two things feed into each other.

The repetitiousness of her work with the dinosaur was very intentional, because that motif draws together the drudgery of her (still cushy) office job and the trapped quality inherent in her being stuck in the time loops. Within any given loop, she isn’t quite conscious of what’s wrong—all she can access is the wrongness. And her work life lets her sink into and explore that feeling, to press it like a bruise, as she tries to get closer to understanding what’s really at stake in her world.

I also just think that’s a realistic quality to office life. We often sort of fall in love with our shitty, comfortable jobs, because they’re familiar, and keep pushing away the understanding that we need a change, because change is hard.

What were you reading (or watching, or listening to), while you were writing End of the World House? Did you avoid other time-travel/parallel universe novels, or seek them out as points of interest? You’re often asked in interviews about the book’s relationship to genre; I tend to think of genre as (1) a messy and not-always-useful category, and (2) as arising from particular traditions/microcanons or relationships to other texts, just as much as the tools or story elements used, so I’m curious about what other works you see as influential on or otherwise connected to this one.

I mostly avoided time-loop and time-travel narratives while I was early on in the writing process, in the same way that I always avoid anything that feels too close to the work that I’m doing; I don’t want to be guided by specific examples unless I need some technical help. But of course I had examples in mind that were already part of my (as you put it) microcanon—not least the movie Groundhog Day, which I just happen to really love. Later on in the revision process, a movie that was very tonally important to me was Being John Malkovich, which is probably closer tonal kin to my book than Groundhog Day, despite the structure.

Around the same time I was reading a lot of science fiction, which is probably no surprise, and a book I found motivating in the clarity of its focus is Solaris by Stanisław Lem (Walker & Company, 1970). I wouldn’t say the books are alike at all, but I did think a lot about the way Lem’s book declares its concept and then ruthlessly follows it, guided by the particularities of his characters.

A selfish question, and not one that you are required to answer: I love the numerous animals of Love Among the Lampreys so much but have yet to find a cephalopod in your body of work. Would you ever draw one, or is it an avoidance on principle?

OK, this question has really thrown me for a loop, because I’m kind of staggered that I don’t have more cephalopods! I found one instance of squid early on, and I suspect that I didn’t return to the tentacular for a while simply because I was trying to avoid repeating myself too much. Later I found one panel with an octopus. But this really feels like a blind spot for me, and I am motivated to fill it. Having a two-year-old, I’ve let my comic fall a bit by the wayside while I work on fiction in my scant free time, but I very much intend to return to it, and now I know what to draw next.

Adrienne Celt was born in Seattle, Washington, and now lives in Tucson, Arizona, where she misses the ocean every day.

She’s the author of the novels End of the World House (Simon & Schuster, 2022), Invitation to a Bonfire (Bloomsbury, 2018) and The Daughters (Norton/Liveright), which won the 2015 PEN Southwest Book Award for Fiction and was named a Best Book of the Year by NPR, as well as a collection of comics: Apocalypse How? An Existential Bestiary (DIAGRAM/New Michigan Press, 2016). Her writing has been recognized by an O. Henry Prize, the Glenna Luschei Award, and residencies at Jentel, Ragdale, and the Willapa Bay AiR. She’s published fiction in Esquire, Zyzzyva, Ecotone, The Kenyon Review, Prairie Schooner, and Electric Lit, among other places, and her comics and essays can be found in The New York Times Magazine, The New Yorker, Catapult, Vol. 1 Brooklyn, The Rumpus, the Tin House Open Bar, The Millions, and elsewhere.

She publishes a webcomic (most) every Wednesday at loveamongthelampreys.com.