On Craft: Rebecca Bernard on Plotting Character

4 Minutes Read Time

Managing Editor Lisa Ampleman: I’m a big fan of Rebecca Bernard’s story “The Theft” in our fall issue. As an early reader of the story here at the magazine, I was impressed at first by the strength of the voice ( a suburban dad buying paint on his way home, to surprise his daughter), and then floored by some of the events and revelations that unfolded. I’m not surprised that Bernard has some great things to say about how to plot character, and we’re honored to host them here:

Plotting Character

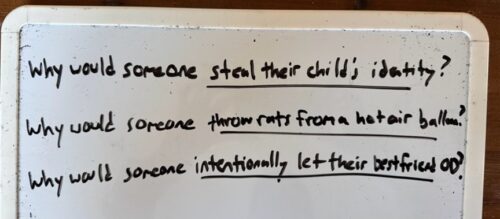

Consider a story exercise via fill in the blank:

Why would a Girl Scout troop plan to attack another troop in the bathroom at camp?

Between my MFA and my PhD, I adjuncted for two years in rural Kentucky and Indiana. The community college where I taught in Kentucky was a forty-five-minute commute twice a week, and to pass the time, I decided I would listen to every episode of This American Life from its outset. This is likely where I came upon episode 209, “Didn’t Ask to be Born,” and its segment on Brent Runyon and his memoir, The Burn Journals. In the segment, Runyon reads from the memoir exploring the events that led him to light himself on fire when he was fourteen years old. The self-immolation led to third degree burns over 85 percent of his body.

Flash forward a few years: I’m teaching a multi-genre Intro to Creative Writing course at the University of North Texas, and we’ve arrived at our unit on fiction. Plot, specifically. Never my personal strongpoint in writing, as I tend to be fixated on what’s happening inside my character’s mind rather than outside. For the lesson, I was teaching ZZ Packer’s “Brownies,” with its surprising but inevitable turns and its powerful second climax (how I think of the narrator’s epiphany on the bus). As a class, we’d mapped out the major plot points of the story, discussing Packer’s use of scene, narration, and detail, and the complexity of their interworking.

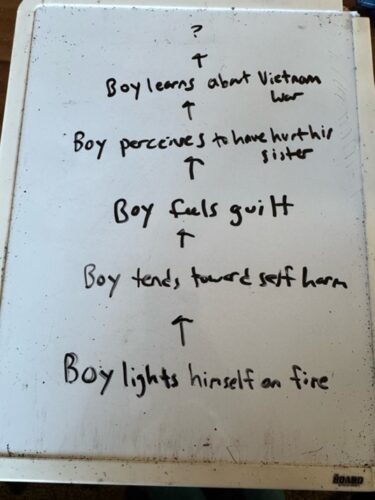

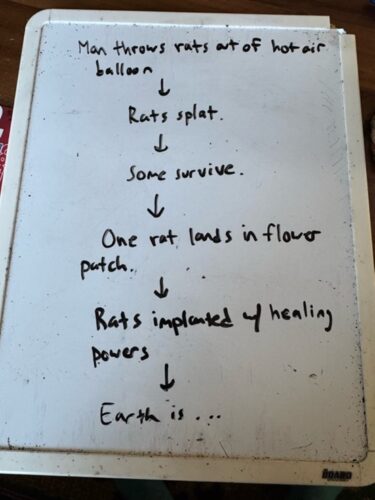

Then I proposed an exercise I called “Plotting Back and Forth.” We’d take a potential climax/inciting incident and work our way backward to understand the motivations, then work past the incident to see its meaning or repercussions. We’d do this first as a class, and then the students would experiment individually using the premise/character they’d created in the weeks prior.

To get us started, I suggested a potential climax—a boy lights himself on fire. I’d been writing stories at the time that explored how we might understand inexplicable and often violent human behavior (what would become my first book), and though I had no memory of Runyon’s actual reasoning for his self-immolation, the act had been percolating in my consciousness. A brutal human mystery.

In the years since, I’ve repeated the exercise with introductory fiction students, working off their suggestions and collaborating with them as a class on the board. Often it becomes slightly silly, but I think this idea of writing our way into understanding ultimately speaks not only to plot but to character, or the idea of character as plot, a concept that Melissa Benton Barker writes about in Craft discussing the work of Mary Gaitskill: “Rather, the character’s interior experience is the action. The character becomes the plot.” Between the exercise and an eventual draft, inevitably things will change, but the practice becomes one way to think through story as a series of events, or decisions made by a character, or the underlying series of whys that helps us into a character. And subsequently we can think through the choices of what to dramatize and what to narrate, what we know about our characters and what will surprise us . . .

From this in-class exercise I ended up writing the story “Boy on Fire” which appeared in Ninth Letter in 2023. And so spun the world in which “The Theft” appears. “The Theft” like most of my first-person forays came from an opening line(s), and the voice and the plot followed suit (with some expert feedback from my workshop at the Sewanee Writers’ Conference). “The Theft” starts with the premise, “What if two boys rob a grieving man?” and the story unravels from there. But as easily it might have been, “‘Why would a man being robbed lie down on the floor mid-robbery?” And with a potential answer comes the story.

Rebecca Bernard is the author of the story collection Our Sister Who Will Not Die (Mad Creek Books, 2022). Her fiction has most recently appeared or is forthcoming in Alaska Quarterly Review, Ninth Letter, and Phoebe. She is an assistant professor of English at East Carolina University.