To accompany our fall 2024 issue (21.2), we have curated a folio on writing about sex (reviews and craft essays) after noticing that several pieces in the print issue include sex, especially the play excerpt by Gloria Oladipo, John Fulton’s story “Emily Leaves Switzerland,” Karolina Letunova’s story “Turn Your Back to the Forest,” and poems by Keetje Kuipers and Jessica Nirvana Ram. We reached out to five writers to get their contribution to the conversation.

Here is Dorothy Chan’s craft review of two poetry books with strong erotic elements:

The Inward Pull and Pulsation:

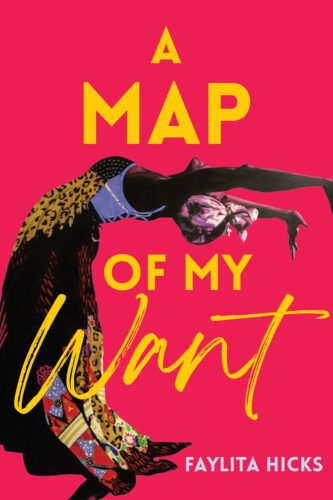

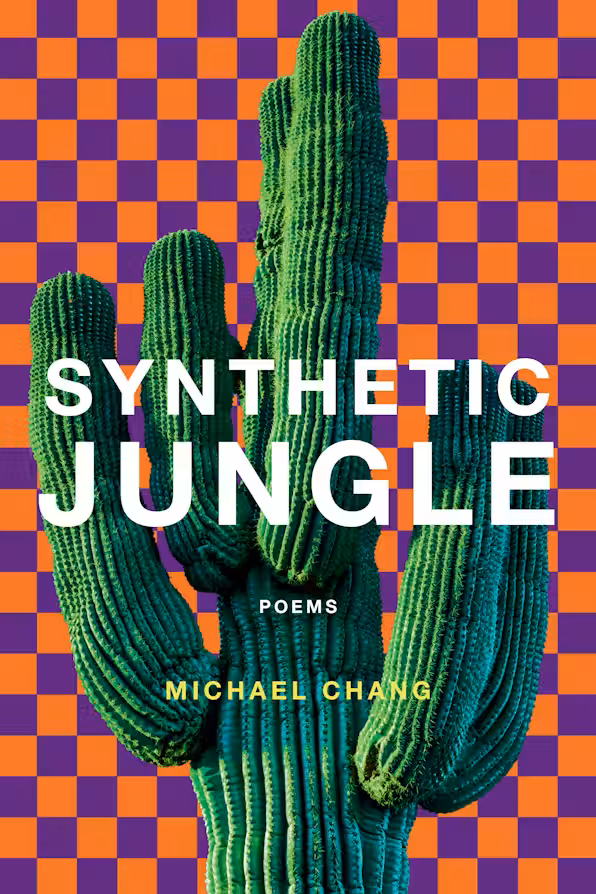

On the Erotics of Faylita Hicks’s A Map of My Want and Michael Chang’s Synthetic Jungle

Synthetic Jungle. Michael Chang. Curbstone Books, 2023. 104 pp. $18.00 (paper)

A Map of My Want. Faylita Hicks. Haymarket Books, 2024. 100 pp. $17.00 (paper)

writing abt sex is hard to do. it comes off as too vanilla on the page: weirdness & a sense of wonder are important. there’s always longing.

—Michael Chang, “Six Bits”

A poem has so much erotic potential. After all, poetic form is defined by movement: longer erratic lines can dance sexily on the page; repetitions are often romances reexplored; and short, syncopated lines can read as witty as flirtation. We could think of the line break as the breath/release after intense physical pleasure. Michael Chang’s Synthetic Jungle, from Northwestern University Press’s Curbstone imprint, and Faylita Hicks’s A Map of My Want, from Haymarket Books, take these ideas to the next level, bringing the erotic into the everyday. Longing becomes the fight for queer pleasure within a capitalistic culture. Both books unravel how the queer erotic becomes a powerful tool against heteronormative, patriarchal modes of life. While Chang’s collection is metaphor for what’s on the body, Hicks’ collection reveals what’s in the body, within the backdrop and urgency of queer Black femme poetics and feminism. In a hard world, how can we as queer people of color reclaim pleasure, from sex and even sharp wit and fashion? How can we be more present in our bodies when experiencing pleasure, and how do lines of poetry swerve into the erotic? I’m also interested in the infinite ways we can write about sex uniquely without forgoing sincerity.

Urgency and Swerving

“Uses of the Erotic: Shifting Timelines” early in Hicks’s A Map of My Want is an example that illustrates the urgency of the body, in this case through self-pleasure. The poem has an epigraph from Audre Lorde’s “Uses of the Erotic: The Erotic as Power,” which ends with an emphasis on “ris[ing] up empowered.” The need to do that sort of rising up surges through the body immediately in the poem’s opening lines:

I feel the water before the water reaches me—a mirror

of my own urgency slipping past the bank, the curb.

The water/urgency runs into “the curb, / and into each of the cars in the lot,” the body responding to the erraticism of nature. As Audre Lorde emphasizes that the erotic is “power,” Hicks (she/they) takes this exact theory and puts it into practice. The body is responding organically to natural disaster, and part of that “natural response” is orgasmic: the need for self-pleasure, cementing perseverance.

The erotic then becomes a way of coping with the flood:

Dripping, I pet

the cat, then the dog, grab the leftover Barefoot wine, and fuck me.

Dripping also becomes a metaphor for the act of self-pleasure, and once again, nature and femme bodily pleasure work in simpatico, within that:

It is the screaming laughter of the neighbors running

in their flip-flops to their doors on other floors,

the crackling sky flipping switches of light across

my living room’s yellowed stucco, the pounding chords

of the monsoon positioning itself right over the lip of my porch,

and the milky slip of the evening’s sun peaking through

the cloud’s erratic smoke that makes me flare violently

on the couch.

The sequential actions of these lines, while the speaker is living in the physical moment (part of the now quality of Hicks’s poetics), tease the small moments of release before climax happens. Hicks emphasizes the emotions leading up to climax, how orgasm becomes achieved. The peeking/peaking here is both a visual image and sexual, the body embracing itself. In self-pleasure, there’s really no limit. Climax can feel as weighty as the “monsoon positioning itself” or as intimate as the play of light on the walls. Hicks’s poetic swerves reflect the urgent swerves of the body.

Chang (they/them) uses poetic swerves, especially through their signature non sequiturs, that emphasize the urgency within queer sex. In Synthetic Jungle their poetry is like a tongue-in-cheek glossy runway show where everyone is beautiful. And like all high-fashion designers, Chang writes pieces that reflect a larger political and social backdrop, including through skillful pop-culture references. Or to channel Michael Kors on early seasons of Project Runway, the “model” (metaphor for the “line”) turns the corner, and the audience gasps, because here is where the volta happens. We feel the wit of the poem’s argument.

Take “Rasputin,” which ends with these three lines:

i just want to be slightly beautiful & lightly educated

|

up-&-coming [ ???? ]

|

no, i came [ !!!! ].

I love Chang’s clever play in “up-&-coming” and “came.” I also want to draw attention to the kenning, a term I learned from my brilliant mentor Alberto Ríos, meaning the compounded word “up-&-coming.” Along with the hyphenation, the use of the ampersand speeds up the delivery of the line. In addition, Chang’s signature text-speak, “[ ????]” and “[ !!!! ],” makes the poem move faster. In sex, we speed up and slow down with both ourselves and our partners through various stages of intimate experimentation. Chang’s poetic equivalent of the sexy “speed up” and “slowdown” and “come down” happens in their inclusion of symbols, from the kenning to the text-speak mimicry. “Coming” as the end of the poem also illustrates tension and release, which poems, like sex, rely on. I’ve always argued that the mark of a strong poem is that the last line lands on one final volta. After that, the reader “breathes” and is then seduced back to the beginning, ready to go again. “no, I came [ !!!! ]” is the cheeky, seductive victory—it’s the aha moment of the poem’s ending,declaring the speaker’s status as an “arrived” writer rather than “emerging,” as well as a sexual satisfaction.

In addition to non sequiturs and text-speak, Chang’s nonchalance is gold. I love this phrase from section 5 of “Six Bits”: “i’d rather fall in a swimming pool than fall in love.” Here, Chang comments on the societal pressures that place romantic love on a higher pedestal than platonic or familial love. Their wit is also a turn-on. For example, I want to bask in Chang’s poetic shade: “how are your fuccboi sonnets” (from “White Ford Bronco”).

The Liminality and Decadence of Non-Heteronormative Sex

The erotic cannot be divorced from political and social contexts. Sex, like poetry, is a potentially liberating act, especially in the liminal spheres of pleasure that are tied to rejecting modes of heteronormativity.

The end of Hicks’s poem “Finger Hut” is one primary example. After a session of self-pleasure “beneath Netflix,” the poem’s speaker rests.

In the shower afterwards, I say

to myself Congratulations.

Your limits have increased.

Turn the dial all the way up

and wait for the heat to find me.

I admire the way Hicks lands her poems in final lines. Here, the “wait for the heat” once again emphasizes the “peaking” and pleasure. I keep rereading the tongue-in-cheek tone of “Congratulations. / Your limits have increased.” By forgoing heteronormative standards of sex, the speaker welcomes more “steam” into their life. Self-pleasure in the shower becomes steamier than penetration, and her “limits have increased,” as she revels in creative modes of orgasm. And why not include humor and cheekiness in all forms of sex?

“#LoveMachine,” the poem directly after “Finger Hut” argues a central idea of the book:

I say “my body loves their body” and the editor corrects me

“the word ‘body’ is dehumanizing” and of coursethe editor is correct—that a body is not the same as a person

but I wasn’t talking about people. I wastalking about the body I arrived to the afterparty in—

the one Velcroed to my person, trying to Velcro to other persons.I say “my body leaks when it sees their body” and the professor

gets hard around the mouth at my obsession with fluids and bodies,says “there is nothing new here” and of course

the professor is correct—that there is nothing new.I like all of my things worn in—

except for my technology

Hicks’s speaker defines the body as erotic, as the vehicle within the liminal space that leads to action. She opens by setting up what is “correct” and what is “new” in relationship to discussions of bodies and sexuality. When they affirm “there is nothing new” and “I like all of my things worn in,” the poem becomes even more significant. For the queer femme to become a #LoveMachine, she first acknowledges how the existence of the body and its capabilities is nothing new. She distinguishes how while the “the word ‘body’ is dehumanizing,” when discussing sex and sexuality, being fully present in one’s body in the moment is an integral part. I love how the speaker brings in themes of nonmonogamy and polyamory: when the body is “worn in” and has more consensual, pleasurable experiences, then the body and the person is ready to continuously find new sexual joys.

Within sex, we find decadence. Within sex writing, lines guide us towards pleasure. I’m basking in the luxury of “Things I Do in a Storm”:

v.

Read only the books with red covers, the warmth

an illusion to convince me that I am alive

in the world, a part of the words constructing the worlds

where streets are filled with strangers

making memories or mistakes,

where I am sitting on a rooftop in Colombia or

catching a taxi in Manhattan or making sweaty love

on silk sheets in Shanghai. So hot . . .

Red, the opening color, sets the mood for sensual delights. The body travels through the erotic across cities all over—the decadence in the scene becomes an affirmation of queer delights and holding onto the “sweaty love / on silk sheets” through every moment.

Chang, like Hicks, works with liminalities of pleasure, but through (seeming) non sequiturs instead of decadence and in an emphasis on the body. For example, here’s the opening of “Cavalli Lounge Lizard”:

in my delirium i thought abt all the war stories you never told me

i am better now

arranging hookups on yelp, smashing my pussy

chinatown a horrifically boring movie

i found veronica mars insufferable

don’t pee on my leg & tell me it’s raining

womxn love to touch your leg but maybe they just sense you need a hug

you are also hot

slick like mercury

small flame sweet swan

the quiz says i could be a wolf or a dolphin.

I admire the aside of “you are also hot,” which takes us into line associations and leaps—ones that celebrate the queer and the sensual: slickness, mercury, animality. When the line “arranging hookups on yelp, smashing my pussy” is followed by “chinatown a horrifically boring movie,” it might feel like a non sequitur. However, they are unified through an opposition to the white cis heteronormative patriarchal standards. I adore the bravado of “smashing my pussy” followed by the calling out of toxic-white-male cinematic themes of Chinatown (but Faye Dunaway forever). Through these slick associations, Chang establishes an analytical connectivity: in a world where we can call out the traditional canon of cinema, we can also show an outward joy for non-heteronormative modes of sex. And we can do so excessively.

In one more example of decadence and luxury, I connect with Chang through glimpses of Hong Kongese culture, like in “Best Buddies, 1990”:

In British Hong Kong the most treasured housewarming gifts were Danish butter cookies in blue tins. These were, oddly enough, available from any of the pharmacies that dotted the island, the rough equivalent of Duane Reade or CVS. &, just as weirdly, it felt like the height of luxury. After the cookies were gone the tins would be used to stash sewing sundries & petty cash

Sincerity is the root of strong poetry. As a child of immigrants from Hong Kong, this homage to the Danish butter cookies in blue tins put a big smile on my face. I find joy in poetry about sex. I also find joy in a poet describing the quirks of their culture. Poetry, especially works by QTPOC artists, reminds me of the immediacy of this now.

Endings

Excess is exactly how Hicks closes their astounding collection, with the seven-page title poem, “A Map of My Want.” Here’s the opening couplet of Section II:

Once, I was a womxn.

Am now an arc, a memory

This poem is a feat. The volta from “womxn” to “an arc, a memory” encompasses queer desire and gender fluidity. The poem later emphasizes the holiness of self-pleasure:

The sound of myself lapping

the lapping of myself—in an unending ritual

of salutation and praisefor the tangible chaos

I wear like galaxies in the skin.

There’s an expansiveness to Hicks’s sequence. Chang’s final poem in Synthetic Jungle, “Working Stiff,” is minimal in form, but its expansiveness lies in the generosity and sexual playfulness of its final lines:

the last thing u see

fit into my crabhole

that dick, all at once

high as u can reach

will that be everything

I adore how “everything” is their collection’s final word, with no ending punctuation, which leaves the suggestiveness even more open, taking us into endless volta. I feel the liberating movements and the femme body and psyche in Hicks’ masterpiece, A Map of My Want. I feel the high-fashion-queer movements of Chang’s poetic runway, Synthetic Jungle. Yes, “writing abt sex is hard to do,” but Faylita Hicks and Michael Chang truly gift us with some scrumptious, meaningful delights. It’s time for us to enter without hesitation.

Dorothy Chan (she/they) is the author of five poetry collections, including Return of the Chinese Femme (Deep Vellum, 2024). They are an associate professor of English at the University of Wisconsin–Eau Claire and cofounder and editor in chief of Honey Literary Inc. Their work has appeared or is forthcoming in The American Poetry Review, The Academy of American Poets’ Poem-a-Day, Poetry Society of America, Literary Hub, and elsewhere.