It’s been awhile since we published recommendations to writers based on what we’re seeing in our submission queue (our Submission Trends and Tips series), so I polled the staff at a recent meeting. Here are some things we’d suggest avoiding, because we’re seeing a lot of them these days:

Braided essays

Don’t get me wrong: I love a good braided essay. I’ve even written some myself! But we’ve seen an overabundance of them in the submission queue. This subgenre feels like it’s become dominant in the field, so you can stand out if you try other structures. Some recommendations for things we see less frequently:

Chronology under tension: Describe events in order, but have something at stake so that the readers keep reading, perhaps a dissonance in what the narrator of the essay knows or a stressful scene so that we want to know how it turns out. As Tim Bascom says in a Creative Nonfiction craft piece, “Narrative essays keep us engaged because we want answers to such questions. The tension begs for resolution.”

Hermit crab: Brevity has a great (“meta”) FAQ about this form in which an essay uses a different written genre as the shell it steps into.

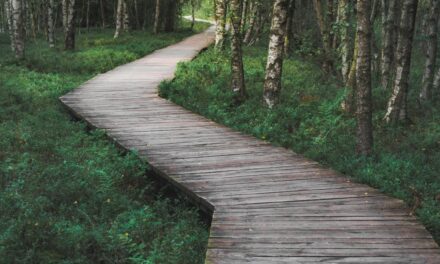

Meditative mind: Think Montaigne, a mind at work. The movement in this kind of essay is associative or following a line of argument.

The tools of writing fiction. As our Literary Nonfiction Editor Kristen Iversen says in her Substack (and elsewhere), literary nonfiction writers “think like a poet, write like a novelist, tell the truth.” If your essay were a fictional story, how would you structure it? We like Lori Yeghiayan Friedman’s suggestion in a Hippocampus Magazine article to think of a work in progress as a comic book, a series of panels of visual images. And elsewhere on that site, Kathy Pooler details techniques to help storyboard your essay as a three-part character arc or a timeline with turning points.

Narrative points of view that don’t ring true

We don’t think you need to only write what you know, but we have seen a lot of fiction that features characters who feel under-discovered, in a way. One major category of these are older people. If you’re writing a story in the point of view of someone 65+, be wary of using dementia as a technique or a “get-off-my-lawn,” “back-in-my-day” personality. Hadley Moore avoids that move in her story “Wait It Out,” which appeared in our Issue 21.1 (read an excerpt here). Her narrator, Judy, is the subtly snarky rebel at her assisted living home (we love her line, “Good luck with your little book”). She discusses the experiences of being older, but the story’s subject is broader than that.

In the same vein, both stories voiced by children and essays about childhood seeped in nostalgia and without a critical lens are hard to pull off well. It can be difficult to convey a believable child’s perspective without becoming sappy or portraying things unrealistically for the age of the character. We’ve found some great prose about childhood, including Sarah-Fawn Montgomery’s essay “Playing House” in Issue 20.2, which includes first-person present-tense scenes set in childhood (see her read part of the essay here), and David Ryan’s story “Three Dreams” in Issue 20.1, which features, in part, a third-person close perspective of a young boy who is building a short-wave radio with his father. But more often in our reading queue, we see less skilled ways of addressing younger voices.

Similarly, if you’re writing about working-class characters, realize that we’ve seen many, many stories in which their lives are portrayed negatively or sentimentally. In stories like these and the ones above, they often become more about that identity category and stereotypes associated with it rather than a character who happens to have that identity but is in a plot about something else altogether. In our Issue 16.1, Adam Latham has a fantastic story with working-class characters, “The Goddamn Sorcerer of Love” (read an excerpt here). His protagonist, who sells secondhand romance novels at flea markets, is worried about losing his girlfriend to someone else and about coyotes in the area. The story isn’t about his class status but about those tensions.

Not in the same category exactly, but akin to it: try to write beyond the expected villain, like a manipulative billionaire (a la Glass Onion) or scheming ex. Unless you’re writing satire, a more complex villain is always more satisfying. In our Issue 20.2, Brock Clarke’s narrator in “Customs & Alterations” (excerpt here) has as an enemy the office that issues death certificates, and in “Sunshine Skyway” by Tierney Oberhammer, the narrator’s enemy is her own mother (excerpt here).

Poems about writing poems, or prose about being a writer

While metafiction and metapoetry can do some amazing things (think Kurt Vonnegut or John Ashbery), lately we’ve seen a plethora of poems about the experience of writing a poem, and prose about being a writer. Not all of that prose is metafiction, exactly, but the stories or essays might be set in a creative-writing MFA program or be about a struggling writer. The poems often describe the inspiration for the poem and then how it was composed. Any poem that’s an ars poetica for another poem fits here as well, and poems in the form of a cento or written “after” another writer also have become very common.

Another alternative for content: become obsessed with something and dive into it as a subject. I became fascinated with space and spaceflight, and it led to my latest book of poetry. Assistant Managing Editor Bess Winter is drawn to dolls, with various angles of interest that support her creative work.

I see this move in our contributors as well: In Issue 21.1, Mandy-Suzanne Wong’s story “Notes from Underwater” shows an intense interest in mussels (read the story here and see evidence of that interest in her essay on our site too). Poets Michael Dhyne and Dean Rader both wrote about the work of the artist Cy Twombly (here’s a conversation between those two) in Issue 20.1. And essayist David Lazar spent time with Oscar Levant and Oscar Wilde in his essay from Issue 17.1.

The trends described above are all just harder sells for us, to be frank! We do see good versions of these moves all the time, but we want to let you know that our inboxes have been saturated with pieces like these. Your work will feel more distinctive and compelling if it goes in other directions.

We’re open for miCRo submissions right now and will reopen for print-magazine submissions on December 1.