11 minutes read time

Assistant Editor Andy Sia: Welcome to our Emerging Writers series! In this series, we engage with the work of emerging writers through interviews, reviews and other forms of close reading. We take a broad view of the term “emerging writer.” Primarily, our goal is to highlight writers whose work has not yet garnered wide recognition because of various reasons: distribution means, geographic location, profession and proximity to academic spaces, recency of debut, number of existing interviews or reviews, and more. In doing so, we hope to support a vibrant and growing literary ecosystem.

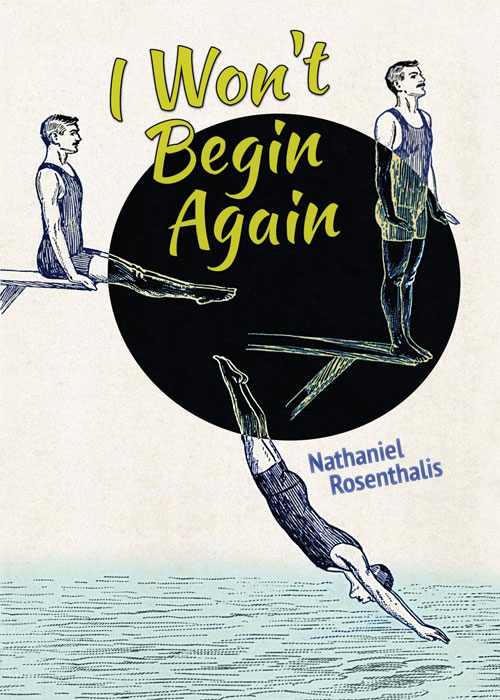

Our first feature is Nathaniel Rosenthalis. I first encountered Nathaniel’s work through his debut full-length collection, I Won’t Begin Again (Burnside Review Press, 2023). I was taken by the language, which seems wholly expansive: simultaneously laconic and ornate, glittering. There is a grace that belies the intricacy of construction—the metered forms, the sharp syntax, the wild and purposeful leaps. Reading the book feels like an encounter with music; so, the thinking on art, time and timing, and perception, is charged with music. I reached out to Nathaniel and am glad to have the chance to speak with him about the book and his creative process.

Hi Nathaniel! Thank you for taking the time to speak with us. Much of I Won’t Begin Again responds to paintings and visual art, including work by David Hockney, Jennifer Bartlett, Eva Hesse, and Louise Bourgeois. Part of the ekphrastic poems come from your chapbook 24 Hour Air, which responds in full to the sequence of twenty-four paintings by Bartlett, Air: 24 Hours (1991–1992). I wonder if you might speak to how you landed on these different artworks as an organizing principle and how you built toward I Won’t Begin Again as a whole.

These were artworks I found myself drawn to by instinct, but the decision to start responding to art was one I did deliberately to get out of some bad writing habits: being too internal, too associative, and abstract.

Halfway through graduate school at Washington University in St. Louis, where I studied with Mary Jo Bang and Carl Phillips, I realized I had an easier time writing more clearly when responding to something concrete outside of myself. Visual art gave me this realization. I’m the grandson of the Israeli artist Moshe Rosenthalis, so I’ve always loved art and been surrounded by it in the homes I grew up in. Looking at figurative paintings, responding to them, I figured out how to write with speed and lightness about material that felt deeply personal but wasn’t restricted to my autobiographical life experience.

This is one of the great struggles all artists face—how to efficiently and resonantly access the imagination. I know that many artists (poets, actors, etc.) believe that great art must come from one’s personal biographical traumas. I disagree with that, for myself. I take a lot of pride that I operate primarily from my imagination, as a poet, rather than adhering to the outlines of my different painful life experiences. This is why I’ve been able to have a relatively buoyant, steady stream of poems coming to me for many years now without ever feeling strain or fatigue as a writer. I haven’t had writer’s block in a long time because I’ve learned different ways of finding a perpetual sense of play in response to anything outside of myself. Writing in response to visual art, where I’m a character in a painting, is one way I’ve found it easy to access, at will, the great stream of imagery that is always running along inside; that stream runs, I believe, inside us all.

I Won’t Begin Again is very close to the thesis I’d assembled at the end of my second year of graduate school, which I graduated from in 2016. The title for it was All Welcome Come Laden. And then, in 2018, I wrote the prose poem sequence 24 Hour Air that PANK published; I then scattered parts of that prose-poem sequence throughout the manuscript, since I felt I needed to do something to take the book to another level, as a way to give the reader something a little more level-headed and recurring and to unify the manuscript even further.

Relatedly, I am interested in the acts of looking that take place in the book. Looking seems to shuttle back and forth between frames. On one level, there is who looks at a painting. On another level, perspectival distance has collapsed, and the voice makes observations about the world even as they are in it, framed by it. (Eva Hesse’s Hang Up (1966) would seem to explode the frame entirely.) How does art, for you, mediate between forms of looking? How does art go hand-in-hand with “resistance/to notice, so/I did”?

Nicely spotted—the most common way I create ekphrastic work is to turn it into personae work, a method I picked up from Mary Jo Bang’s work, especially The Eye Like a Strange Balloon (Grove, 2004). A painting becomes a stage that already exists, that I only have to walk onto. When I’m on that stage, i.e. inside the painting I’m looking at, all I have to do is behave organically and spontaneously in my verbal energy in response to what is around me in the painting. And that gets my verbal energy revving and high; I get to fabulate, make leaps of associations, through concrete details that I sort of wing in the moment.

Looking then becomes a trigger point for truthful verbal human behavior. It’s funny—before starting my acting career, I never would have described a poem as “verbal human behavior.” But my acting and singing training has given me the framework of drama that I didn’t quite have before. I find a lot of poetry clarified and simplified now that I’ve studied acting.

The behavior of the language in my poetry tends to be dramatic, tends to be that push-pull tension, that sense of “resistance,” as you quote it from the book’s opening poem, “Regards, Only Your Good Boy Violence” (which is a play on ROYGBIV—the colors the human eye can see—another reference to looking).

Time feels surficial, touchy, in I Won’t Begin Again. As I read, I thought of time almost as a three-dimensional plane on which moments, events, and other particularities might crop up, then disappear. This sense of time, I think, also allows for intimacy, a shared time. I read, in another interview you gave, that each of the ten sections in a “A Ten-Minute Moment” is meant to last a minute when read aloud. Poetry is of course an inherently timed medium—you spoke about your use of metrical forms in that same interview—and I love this instance where time so directly and tangibly extends to the reader. What are your thoughts on the connection between time and intimacy?

That description of time as a three-dimensional plane for crop-up events is exactly right! Thank you for so carefully reading my work; you’ve really hit the nail on the head. Intimacy is the water in which the body of time has to swim, or maybe it’s the reverse—time is the only water in which the body of intimacy can swim, if it’s to swim at all. It’s hard for me to say what the relationship between time and intimacy is without relying on a metaphor, so I suppose the best I can do to approximate an answer to your great question is to refer you (and myself) back to the poems themselves! Maybe this one, published in Granta and in my second book, The Leniad?

Because the poems are compressed ways of thinking and feeling, with purposeful multiple meanings in them, they can say a thing better than I can, consciously.

In addition to being a writer, you are a singer and an actor. How do your other creative endeavors inform your writing, and vice versa?

Right now my performing and my acting are coming together to inform my new manuscript; its working title is Hi, It’s Me, Orpheus.

In this manuscript, Orpheus raises his voice like a rock singer (rather than a typically sweet-voiced bard) to grapple with his part in losing Eurydice: “Add vice to your own good and you get a voice like mine, with distortion.” The idea of doing a more contemporary Orpheus was inspired by Reeve Carney, who originated Orpheus on Broadway.

My Orpheus works in a coffee shop, walks the city with AirPods in, fills out a worksheet for himself on how to act the song before performing for Hades to secure his beloved’s release; the worksheet has questions Orpheus, like any good singing actor, has to answer: who are you talking to in your song, how you are trying to change them? What’s getting in your way? What’s happening in the moment before you start singing? I picked up this way of working from the Meisner-informed acting coach David Brunetti’s book Acting Songs. I love this talismanic line of his: “Don’t be interesting. Be interested. Get someone to change.” It clarifies for me much of what makes great art.

And Eurydice isn’t a “songbird” the way some sentimental retellings would have it; rather, in my version, Eurydice is an essayist who covers words with a “burned air,” who lives tartly from beyond the grave, in pieces of text Orpheus must come to terms with: “But this is what the underworld is like,” she tells him, “a lack of a camera starts a close-up of your forehead to track a thought, in a way that won’t stop. A quality of mercy is shot. . . . And now I can’t forget.” This Eurydice is partly inspired by Eva Noblezada’s Eurydice, which she originated in Hadestown as well.

In both of what I quote here, cinema and vocalizing become the material of metaphors for these characters. My versions are pretty distinct from Ovid’s, the versions that appear in Hadestown, and in other retellings, like the work of Mark Strand and Louise Glück’s. Acting and singing inform the claims of the poems themselves; the immediacy of these two art forms also is pushing me to clarify the poems in a way that I never would have in my previous three books, I don’t think.

There are some technical considerations in the overlap of acting/singing/poeming. I can talk for hours about vocal technique and acting technique, so I’ll be brief; it boils down to preparing before the actual moment of performance/writing, and then letting go in the moment, letting whatever is around me do the lifting, as it were.

The best book about this subject—and it’s one I’ve recommended to several poets I’ve taught or advised—is The Actor and the Target by Declan Donnellan. When I read that book two years ago, my first thought was a wish that I’d read it when I was in graduate school. This book very simply breaks down all the ways actors (and in my view, singers and poets) can be blocked and all the ways to unblock oneself. I’ve become even more unblocked as a poet through the acting and singing work I do. I recommend this book to poets I teach but it would be helpful to anyone who devotes their time to making art—it’s a real clarifier of the sky we all live under.

Nathaniel Rosenthalis is the author of three books of poetry, including The Leniad (Broken Sleep Books, 2023) and Works and Days (Broken Sleep Books, 2024). Individual poems have appeared in Granta, New American Writing, Chicago Review, Conjunctions, Denver Quarterly, and elsewhere. He lives in New York City, where he teaches poetry at NYU and Columbia. He works as an actor and singer as well, having performed Off-Broadway and in storied Broadway venues like 54Below and Joe’s Pub at the Public Theater. He is a proud member of Actors’ Equity.