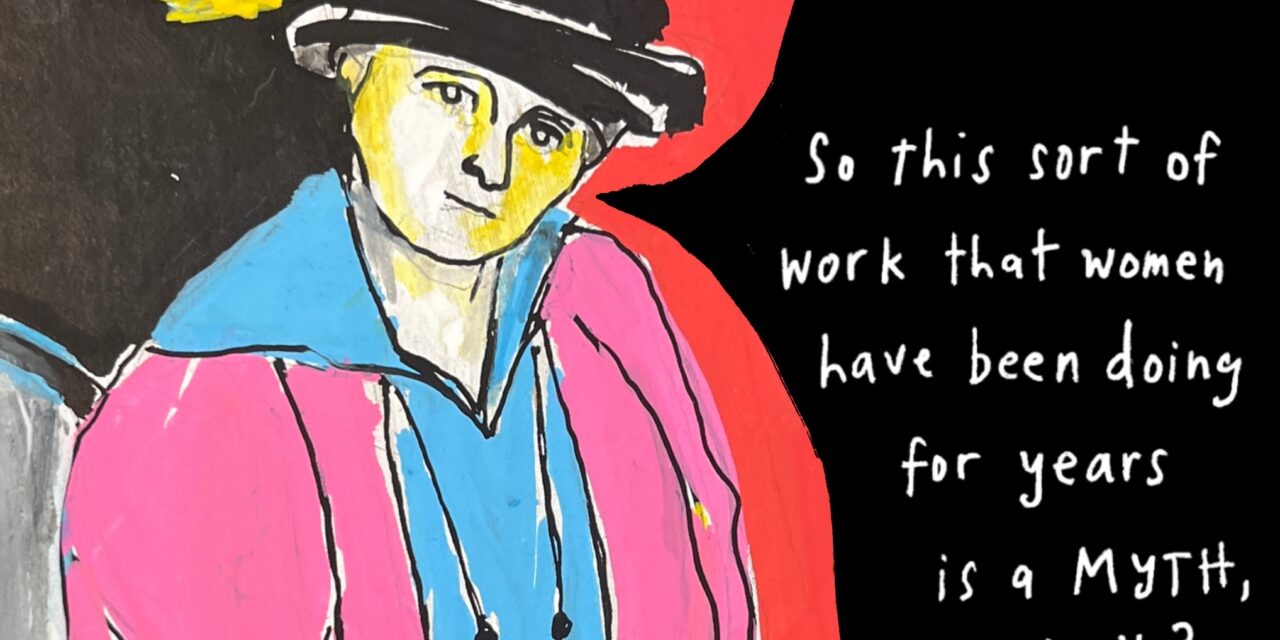

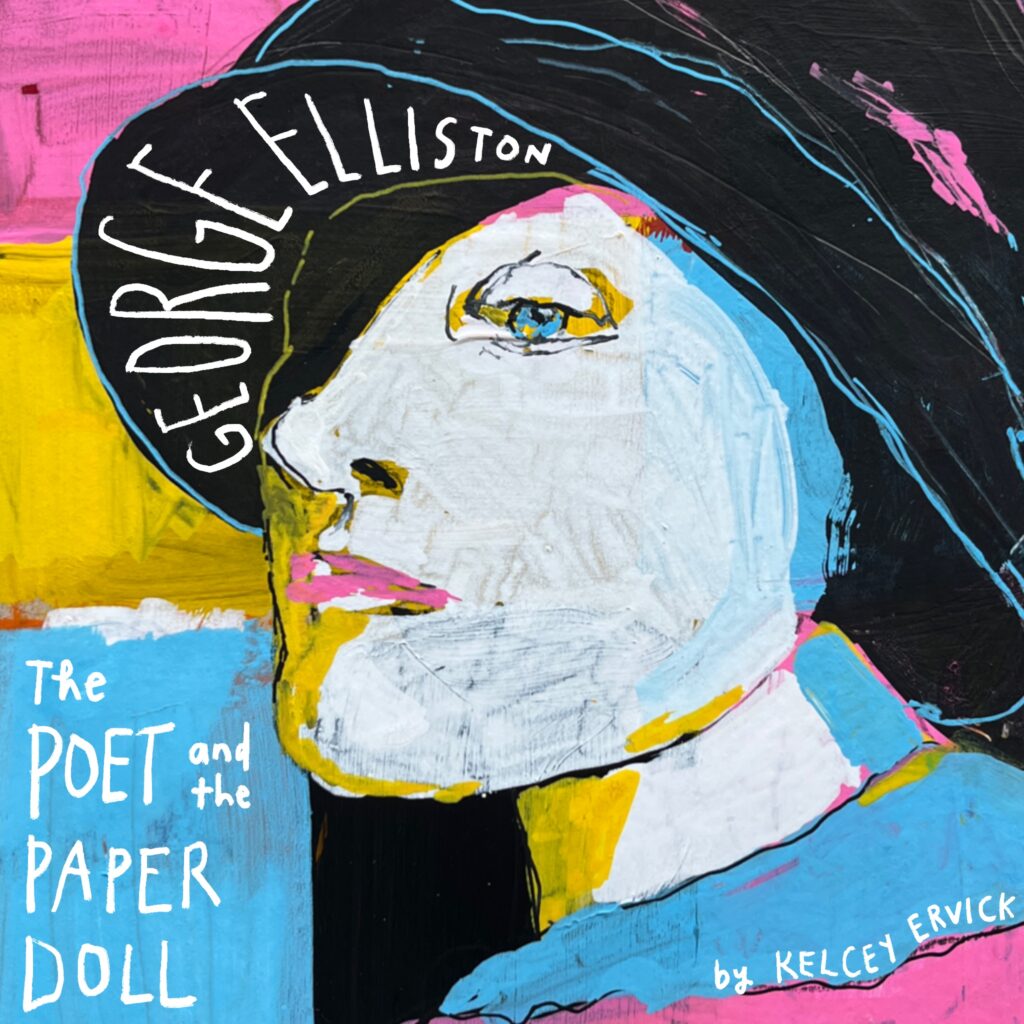

Assistant Managing Editor Bess Winter: We’re delighted to partner with Kelcey Ervick this year just in time for AWP — the Association of Writers and Writing Programs conference — which happens February 7-10 in Kansas City, Missouri. Not only has Kelcey created this beautiful graphic essay especially for CR, but her illustration of George Elliston also adorns our covetable AWP bookfair swag. Stop by booth 912 to buy an eco-mug or high-quality notebook featuring Cincinnati’s very own George Elliston, inspiring woman, poet, and patron of the arts.

The year was 1883. The baby was a girl. The baby’s name: George.

The year was 1900; the girl, now 17, left home. She knocked on the door of the Cincinnati Times-Star. “You’re George?” they asked. She became a reporter.

The year was 1921; the woman, George, published a book of poetry. Over the next several years, she would publish many more.

The year was 2000; a graduate student enrolled in a poetry course, read poetry, met poets. She browsed the ten thousand poetry books in a library room obviously named for some old dead dude.

Except it wasn’t. The George Elliston Poetry Room wasn’t named for a dead dude. It was named for a woman who publicly wrote poetry and secretly amassed a fortune that she left to the University of Cincinnati for “the cause of poetry.”

And it wasn’t until I’d been a graduate student at UC for three years and attended dozens of events in the George Elliston Poetry Room that I learned that George was no dude.

And so, in a class called Writing Cincinnati, I did my own investigative reporting.

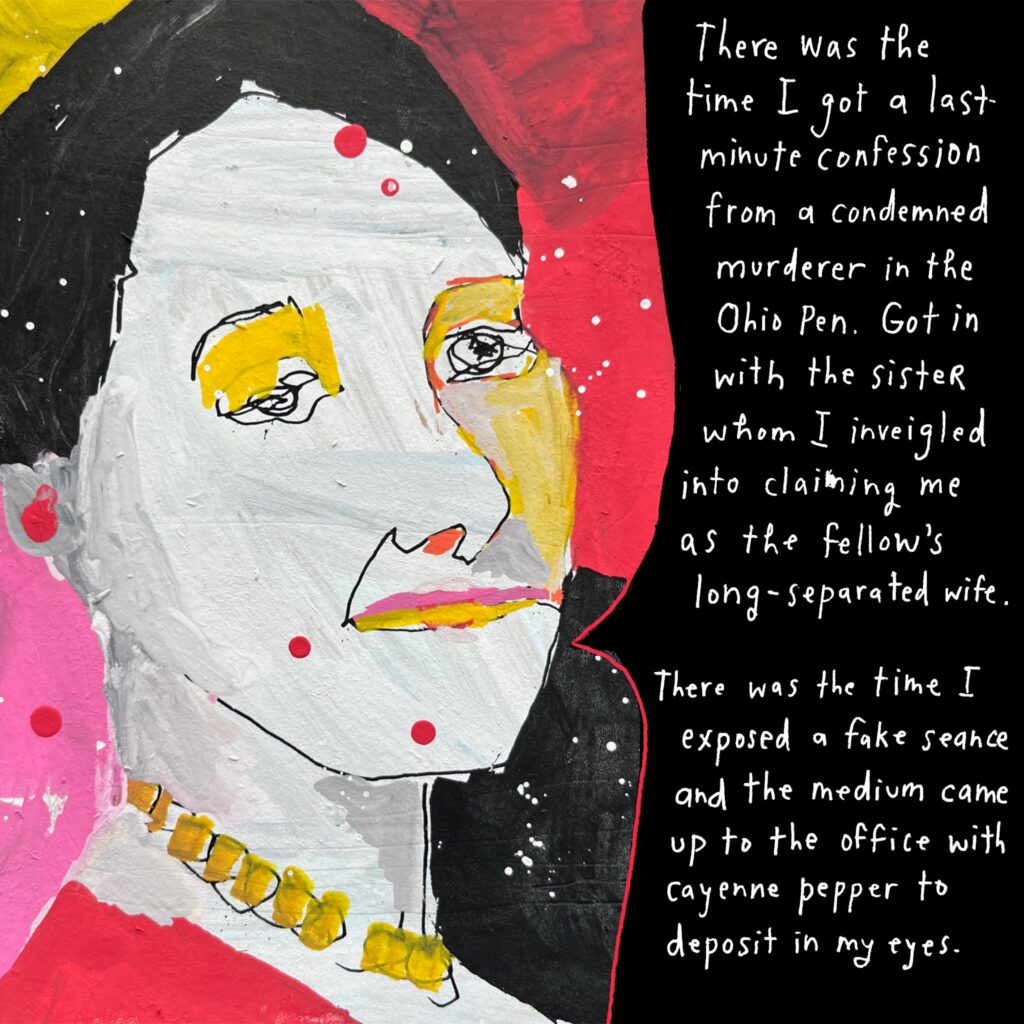

I learned that, unlike George Eliot and George Sand who took pen names to disguise their gender, George Elliston’s given name was actually George—after her mother’s beloved brother. I learned that she was a top-notch crime reporter. When the Saturday Evening Post published a condescending description of women reporters, disparagingly calling them “paper dolls,” Elliston penned a passionate response that looked back on a career comparable—if not superior—to that of any male reporter:

She recalls climbing out of third-story windows, entering a saloon full of men to scoop another reporter, spending a night in jail to prove it wasn’t haunted, and covering the coronation of Queen Elizabeth, “sweating to get stories off the beaten path around London.” She got an exclusive interview with New York Giants baseball manager Mugsy McGraw. “Scarcely a week went by,” she recalled, “that I wasn’t at the morgue taking a . . . very close look at some decaying body in one of the long zinc holders.”

I was so intrigued by George Elliston that I made my first ever research trip to an archive: I visited the Cincinnati Historical Society at Union Terminal where her papers are held.

Early in George’s long and dramatic career, she met Augustus Coleman, a cartoonist at the paper. In 1907, at age twenty-four, she followed him to St. Louis, where he’d taken a new job, and they were married. She created a scrapbook of wedding announcements, letters, and honeymoon photos, which I examined in the archives.

In one letter, her Aunt Dollie reported that George’s colleagues “had not recovered from the shock” of the marriage. No one “could understand how George a man-hater could marry.” One of George’s friends wrote that she “ruined four envelopes” just trying to write George’s new married name. Others expressed relief that George would “have someone to take care of” her. (LOL)

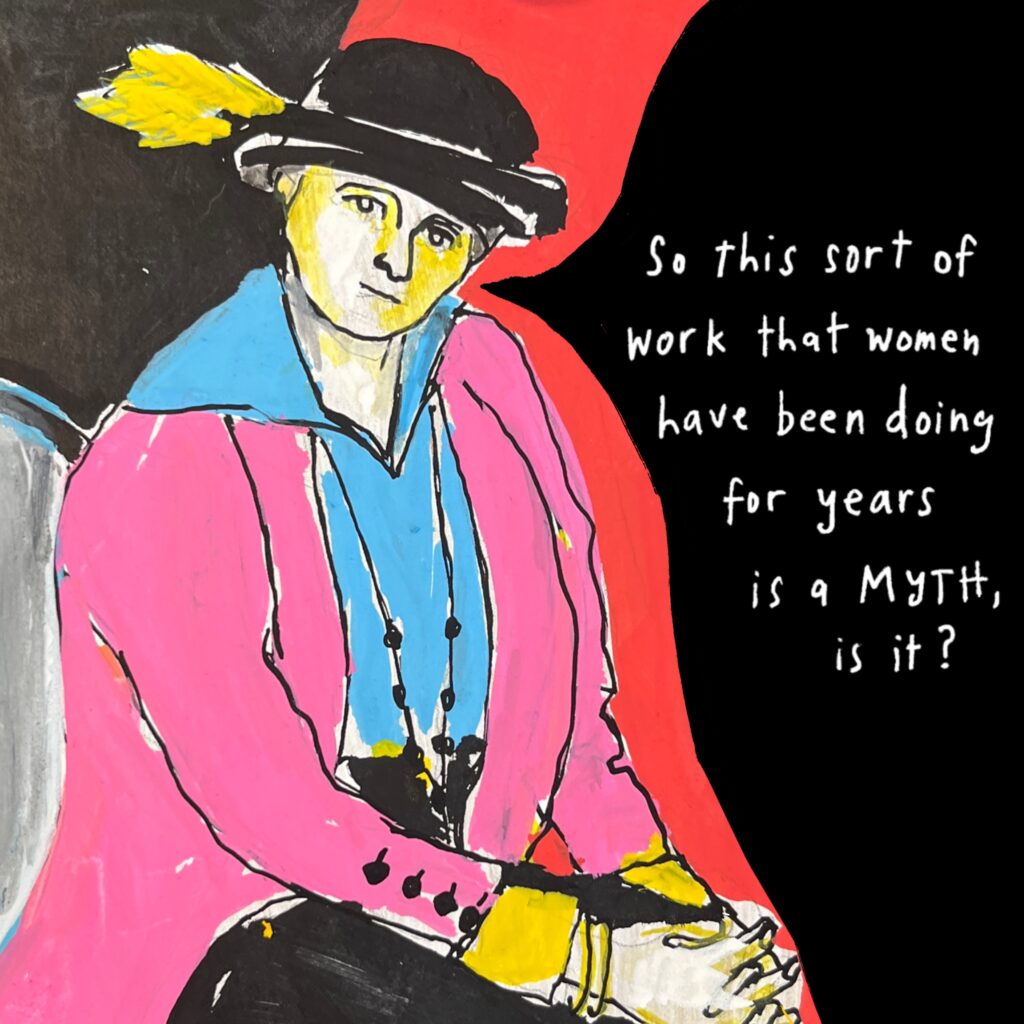

If her friends and family were surprised about the marriage, they may have been even more surprised when, six weeks after the wedding, George returned to Cincinnati—alone—and resumed her work as a reporter at the Times-Star.

The couple never divorced, but they never lived together again.

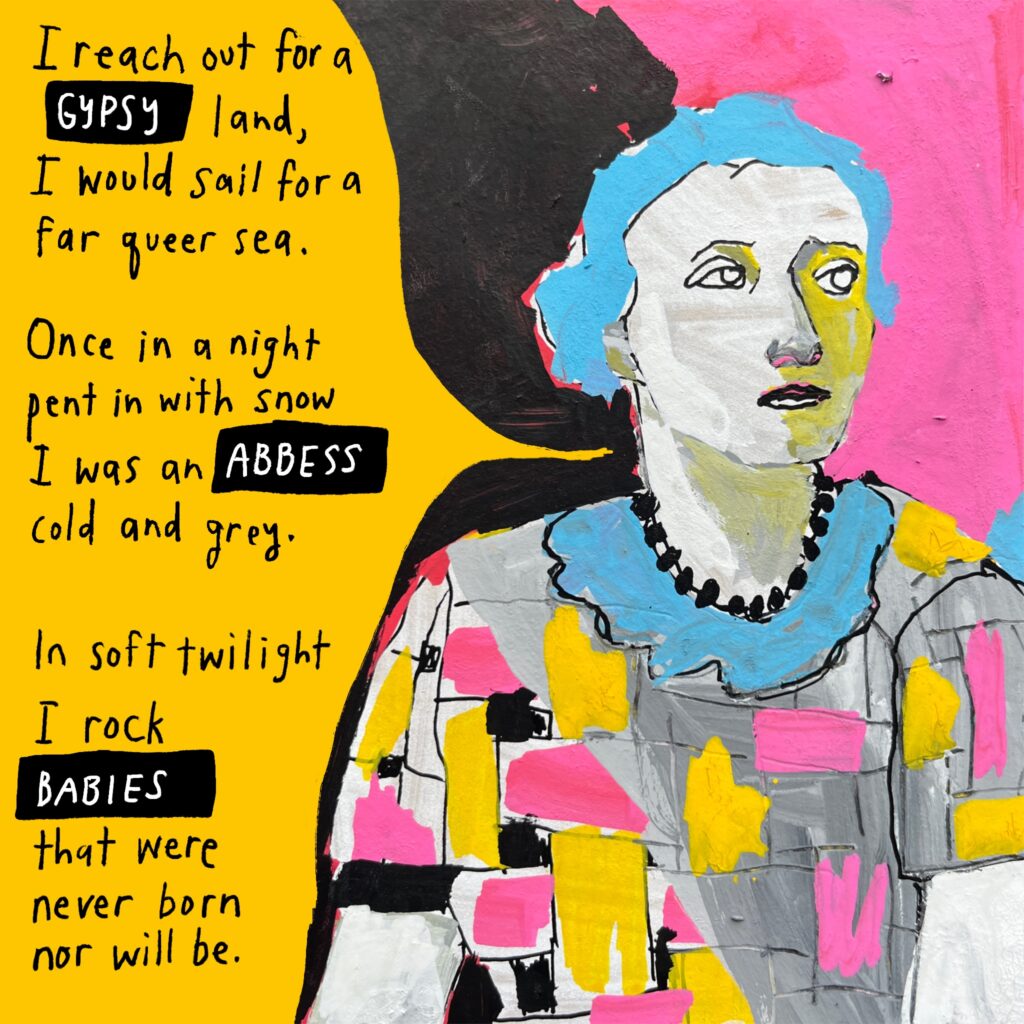

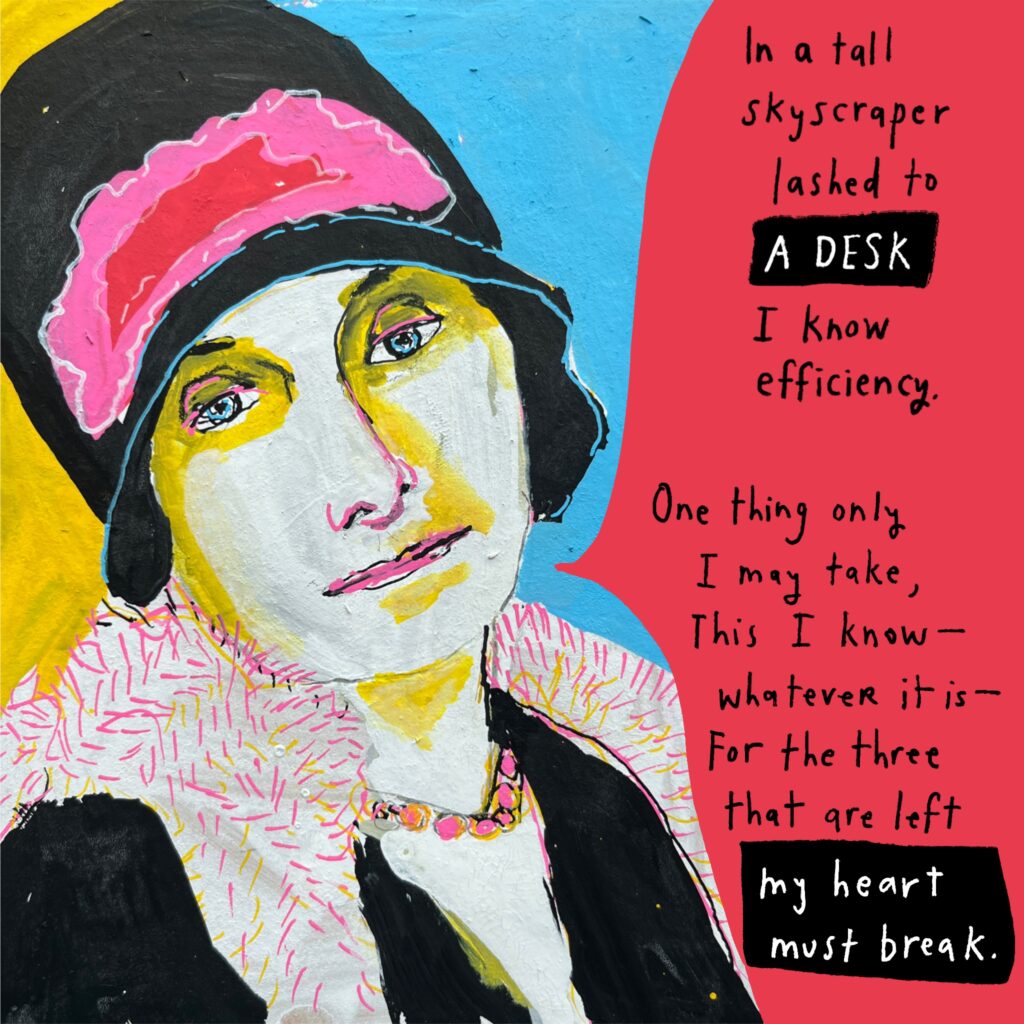

Over the next few decades, “Mrs. Augustus T. Coleman” quietly made a number of significant real-estate investments. Meanwhile, George Elliston wrote and published hundreds of poems, some of which explored her deep longings as a woman. In “Fourfold,” for example, she identifies four paths she would like to take in life—a “gypsy”/traveler, an abbess, a mother, and a journalist—though she knows she can only choose one:

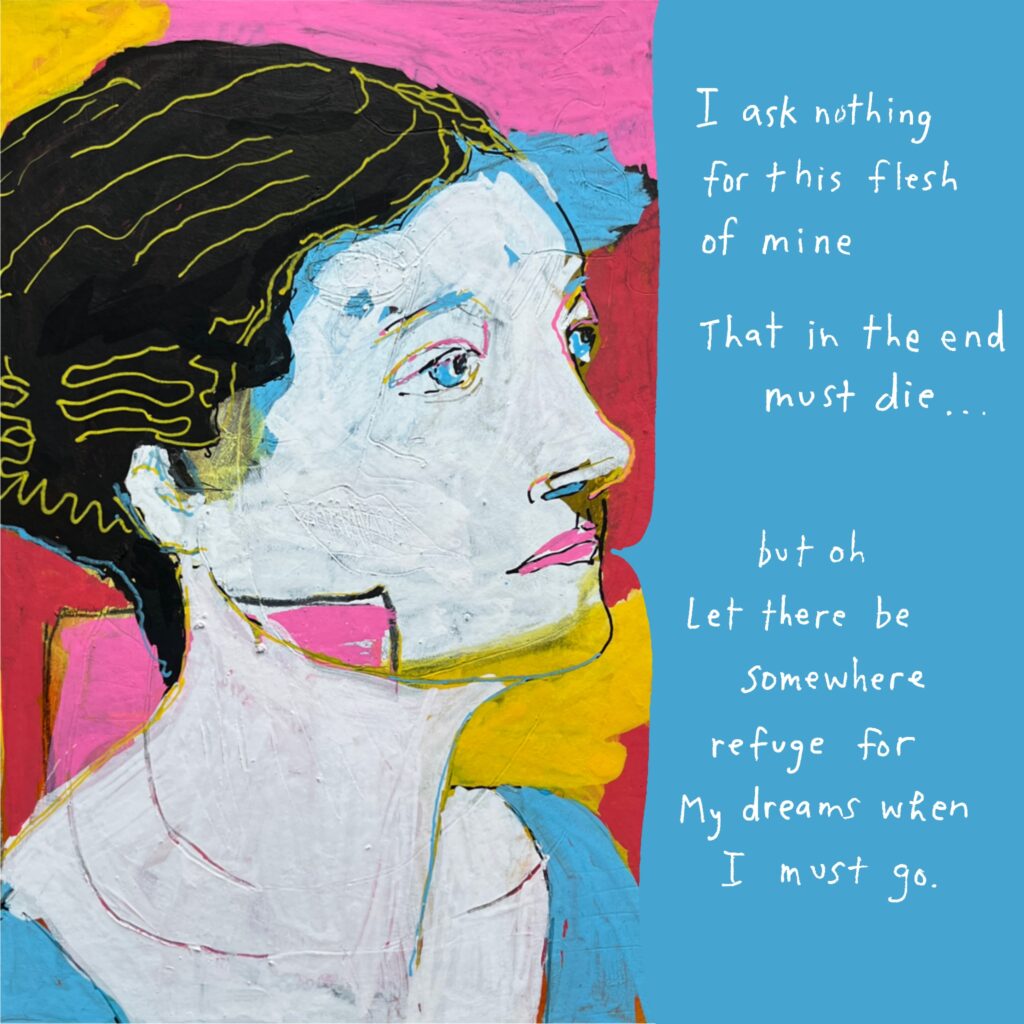

Her poems—often rhyming, traditional in style—were published in newspapers throughout the country, in the literary journal that she edited, and in nearly a half-dozen books translated into several languages. They were set to music by contemporary composers and performed by professional singers. She won songwriting competitions for her verses and had a weekly radio show where she read her poems.

Although “Fourfold” suggests she can only obtain one of her four desired identities (the reporter “lashed to her desk”), she certainly had connections to two of the others. George was not an abbess, but her devotion to poetry was like that of a nun to God, and her poems express the secular equivalent of religious fervor. She desired to be a “gypsy” (a word we understand differently today but which she used to signify a wanderer), and she did in fact travel the world, including Europe and Africa. She was one of the first women in Cincinnati to fly in an airplane. And the name of the poetry journal she edited from 1925-1939? The Gypsy.

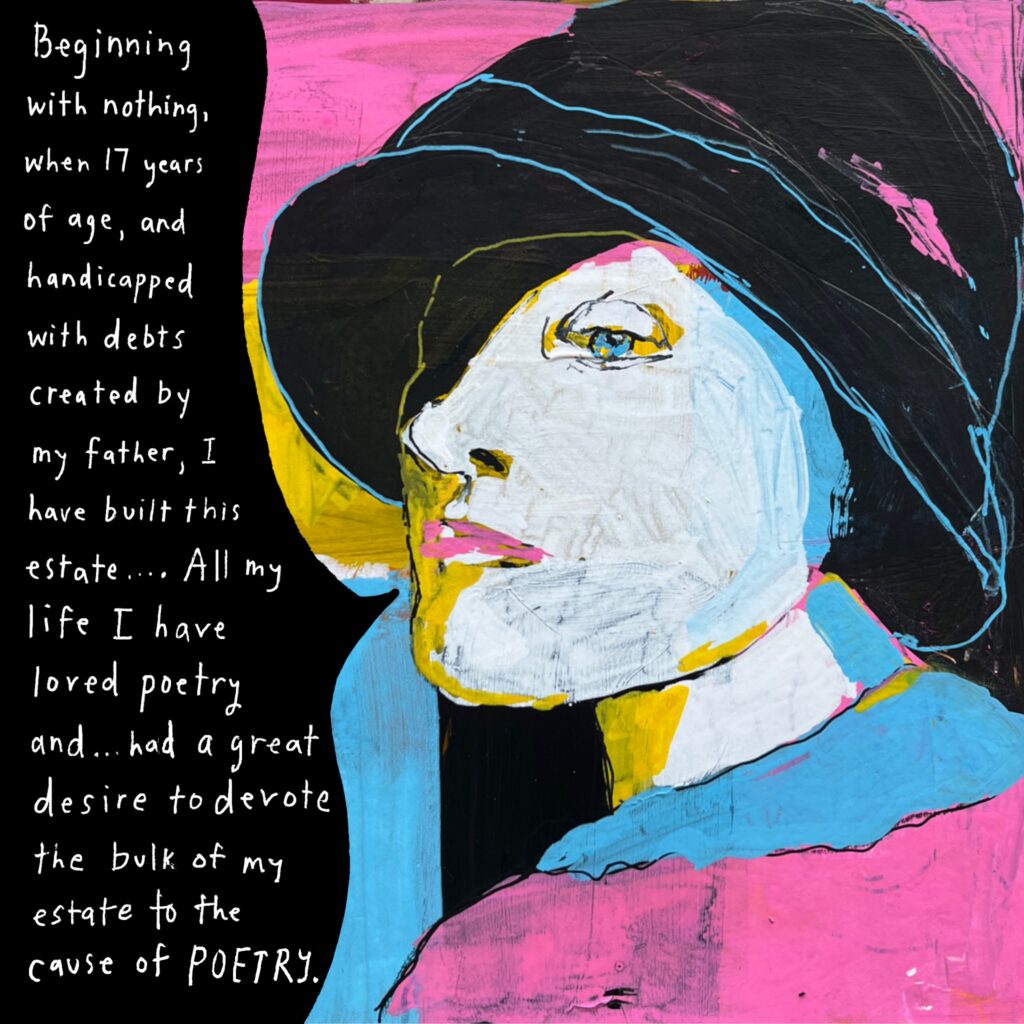

Over the decades, George Elliston amassed a fortune, primarily through buying and selling real estate in Cincinnati under her married name. Some of the properties she turned over for a profit; others she lived, wrote, and held extravagant parties in.

To her two favorite homes she gave alliterative names: “History House” and “Catalpa Cabin.” The former, in downtown Cincinnati, had previously been the site of the Museum of Natural History and before that had served as the Union Army Headquarters during the Civil War. It was old and drafty and probably a bad financial investment, but she made use of the unique space with rental units, personal living quarters, and an event hall for theatrical performances and lectures. “Catalpa Cabin” was a farmhouse outside of Cincinnati where she hosted friends who performed plays with elaborate costumes. She was member of the National League of American Pen Women, and in a 1945 issue of their bulletin, it was reported that she hosted the members of the Cincinnati branch who “delight[ed] in the atmosphere of gay Bohemia that pervades Miss Elliston’s new home.”

No one had any idea about her other properties that she didn’t live in—or the fortune she had accrued.

When she revised her will shortly before her death from cancer in 1946, she “conservatively” valued her estate at a quarter of a million dollars—the equivalent of $3.5 million today. In her will she wrote:

When she died in 1946, she left the bulk of her estate to the University of Cincinnati—to poetry.

Robert Frost (who had previously served as a contest judge for The Gypsy) was a Taft lecturer at UC when the news of the endowment was announced.

“Where is there such another chair in the United States?” he said. “It is splendid for Cincinnati.”

A brief postscript:

On a visit to Cincinnati in 2023, I found a copy of George Elliston’s first book, Every Day Poems (1921) at Duttenhofer’s Books. Inside is an inscription in George’s own hand:

![Painted sketch of a black book titled "Every Day Poems" by George Elliston. The caption reads "I like to imagine that it's inscribed to me." Below the caption is an image of the inscription in Elliston's own hand, with "Kelcey Ervick" superimposed over the inscribee's name. The inscription reads: "To [Kelcey Ervick] who is herself a poet with very lovely thoughts -- George Elliston."](https://www.cincinnatireview.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/GE-9-1024x1024.jpg)

Author note:

Thanks so much to the wonderful Dr. Lucy Schultz who was my professor for the Writing Cincinnati class where I conducted my research on Elliston. I have kept a file of the work I did in that class ever since, and it was such a pleasure to read Lucy’s engaged and encouraging responses to my writing. “You must please publish something about her,” she wrote. Twenty years later, I finally have! I worked on this project with my classmate at the time, Susan Steinkamp, who remains a good friend, and who still sends me texts with photos of my books that she spots in bookstores.

Aside from what I found in the archives, most of what I recount here—especially George’s description of her experiences as a reporter—comes from “A Miss of Contradictions,” a terrific article in UC’s Horizons magazine by UC alum and English professor Iphigene Bettman (George’s acquaintance at the Times-Star). Another helpful article was “George Elliston: The Pattern of My Past” by Donna Wolfe, whose father was a friend and escort to George Elliston and to whom she left her Catalpa Cabin property. (I know, I know: I didn’t even mention that part of the story!) I’m not sure where the essay was published because I only have a twenty-year-old photocopy of it. I was glad to see a more recent article by Steven J. Gores contextualizing the significance of The Gypsy: “Building Cincinnati’s Poetry Community in the Period between the Wars: George Elliston, W. T. H. Howe, and The Gypsy” appeared in Ohio Valley History in 2021. I didn’t refer to it here, but I did enjoy learning that The Gypsy was well regarded and one of the longer-running poetry journals of the time behind Chicago’s Poetry magazine.

The portraits of Elliston throughout the essay are all loosely illustrated from photos found in my file or online. All the quotes are from Elliston’s poetry or quoted in Bettman.

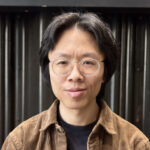

Kelcey (Parker) Ervick received her PhD at the University of Cincinnati in 2006 and was one of the first volunteer readers for the program’s brand-new literary journal, The Cincinnati Review. Little did she know that her interest in George Elliston was not an anomaly but the start of a career writing stories about badass women mostly forgotten by history. Ervick also started adding drawings to her stories, and her most recent books are the graphic memoir, The Keeper, winner of an Ohioana Book Award, and The Rose Metal Press Field Guide to Graphic Literature, an edited guide to making comics and graphic narratives. A professor of English at Indiana University South Bend, she writes and draws about the creative life at The Habit of Art.