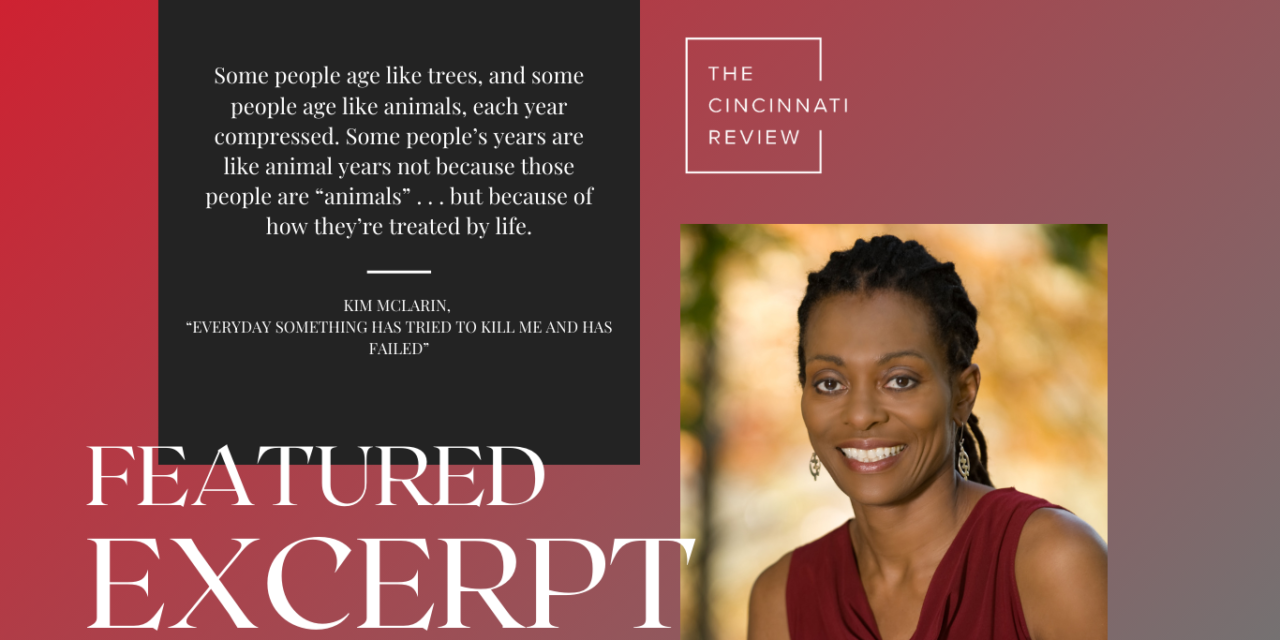

a phrase from Lucille Clifton’s poem “won’t you celebrate with me”

“Don’t get old,” my mother says as I dry her back. It’s not the first time she has issued this warning, not even the first time today. Rolling out of bed in the morning, she reached for her cane, pushed herself to her feet, gave me a little smile. “Don’t get old.”

Helping her put on her shirt, I remind my mother that I have already breezed past fifty, am well along the path of no longer being young. Old age is coming for me sooner than I would like to consider, sooner than either one of us would like to believe. She looks startled at my reminder: how is it possible to have a child over the age of fifty and already nearing retirement? How is it possible to have lived so long?

She never expected to live this long.

“Don’t get old,” my mother says. Sometimes, making my voice high and light, I leap in to finish her thought: “It’s not for wimps, huh?”

“It’s not for wimps,” my mother confirms. By “wimp” she means someone who lacks the strength to do the tough, unpleasant job at hand. Strength of that kind is not a thing my mother has ever lacked, having been handed many tough and unpleasant jobs during her life, not the least of which was raising five children alone. She is the toughest person I have ever known and also the most fragile, unbreakable but easily fractured, prone to chips and cracks and dents. I keep trying to find the right metaphor, a way of capturing a woman who is the opposite of those White southern women they call steel magnolias. My mother is one of those Black southern women who grew armor in order to survive a hostile world but remained as fragile as a robin’s egg inside. A shelter built with crepe paper. A tank of woven spiderwebs. A fortress spun from glass. Something like that.

We finish her shower, an exhausting fifteen minutes for her, no pleasure, all chore. She prefers baths, but climbing in and out of the tub now is dangerous. I rinse out the stall while she shuffles down the hall to put her dirty clothes in the washing machine. I could do this for her, but it is important that she contribute to the running of the household, that she continue to do things for herself. When I first arrived, visiting after more than a year away due to COVID, I tried to do everything, running around the house in a frenzy, waiting on her hand and foot, until she said, “I feel so useless,” and I stopped.

I do not visit enough.

My mother lives with my sister on the other side of the country, the other side of the continent. I take off over the Atlantic and land over the Pacific and drive a rental car to my sister’s house. There are five of us, four girls and one boy, but my sister alone has taken on the burden of caring for our mother. The rest of us try to help when and how we can, but it is inadequate. It is all inadequate.

Don’t get old.

I make lunch: yogurt for me, a turkey sandwich for my mother, strips of meat on bread as soft and white as drifts of snow, the kind of bread I grew up eating and now, in my East Coast arrogance, disdain. My mother loves it still, and anyway, her teeth will not accommodate the hearty multigrain or crusty baguette I prefer, because in America poor people don’t deserve dental care. To the tray I add a small salad drenched in Thousand Island dressing, some chunks of watermelon and cantaloupe, a Snapple tea. She takes her noontime pills, four of them, including vitamins. She has already taken a handful of other meds after breakfast and will take another handful before bed, more pills in one day than I take in months. We watch The People’s Court or Judge Judy, shows that make me simultaneously feel better about my life and despair for humanity. What I know about Judge Judy is that she has been on forever and has made a ton of money and likes to berate people and thinks herself very tough and very discerning and very smart, which, compared to the people who come before her in her “courtroom,” she certainly is. It’s funny how people often confuse being in the right place at the right time with deserving what they luck into, but I will give Judy this: she has spawned an infestation of imitators. Every time I visit my mother (the only time I watch daytime television,) I discover another court show: Judge Mathis (a buffoonish, jive-shucking Black man,) Judge Faith, Judge Jeanine, not to mention Divorce Court and, astonishingly, Paternity Court. Even Jerry Springer gets to play judge for fun and profit in America. Everything about these shows seems petty and grimy and small, a relentless parade of accusation and humiliation and delusion. Especially delusion: people lying to others, people lying, time after relentless time, to themselves. When I ask my mother why she likes them, she shrugs and laughs. The perfect response.

“Put on Dr. Pimple Popper,” she says. Meaning, If you think that’s something, watch this. Dr. Pimple Popper, which I have never seen and which I cannot believe exists, is a reality show with a pretty young Asian dermatologist meeting people with all kinds of horrible, disfiguring skin conditions. She talks gently to them about the impact of their hideous growths on their lives and self-esteem and then proceeds to, yes, pop the pimple or pare the keloid or surgically remove the lipoma the size of a tennis ball dangling on the inside of their leg, all this right there on camera, blood and pus and stitches and all. I am sickened, but my mother watches with fascination. “Isn’t that amazing?” she says. “Don’t you think that’s interesting?”

She wanted, at one time, to be a nurse.

When the pimple show is over, I dig out a checkerboard from the cabinet. The last time I visited I tried to get my mother interested in puzzles, in sudoku, in embroidery. No dice. I long ago gave up trying to interest her in reading, gave up trying to understand why our childhood home was full of books she never opened. I opened them. They set me on my path.

My sister has also given up trying to get our mother to write her memoirs. “I wouldn’t want to depress people,” my mother says when I ask again. Six months from now when I visit, she will have forgotten that she was opposed and say, “I was going to write a book about my life, but I can’t remember it. My memory is so bad.”

She wanted, at one time, to be a writer.

She says yes to the checkers, though mostly to shut me up, I think. I plan to go easy on her, but after listening to my refresher of the rules, my mother quickly captures half my men, lands three kings, then takes the rest of my pieces. I am surprised and delighted and a little chagrined, the competitive instinct being what it is; it’s like the first time your child beats you in something fair and square. I ask if she wants to play again. She shakes her head.

“I’m trying to remember what I did with all my time,” she says.

“What do you mean?”

“I didn’t play checkers, never liked to play card games. I was not a big reader. I’m trying to remember what I did with all my time.”

“You worked,” I say. “You worked hard.”

She nods. “Working outside the house or working inside the house. No time for myself.”

Rocking herself to her feet the way the physical therapist taught her, my mother grabs her cane and heads upstairs to nap.

* * *

I used to think I had a pretty good grip on aging, that I understood and accepted the inevitable. I would not be one of those people who go around saying things like “Age is nothing but a number” (yes, and so is miles per hour and so is blood pressure, and both those things can kill you if the number grows high enough, so what exactly is your point?) or that fifty is the new thirty (it isn’t) or that being around college students keeps one young (they exhaust me.) I would not be like the middle-aged men I dated postdivorce who described themselves as “just a big kid” and who, in fact, dressed like toddlers and acted like adolescents and labeled women their own age “yucky” but believed themselves to be magically, eternally youthful, men who at forty-five or forty-eight still wanted to settle down and have children “someday.” I would not be ridiculous.

I believed my equanimity about aging came from not having loved childhood or adolescence that much. I was an odd outsider child, an odd outsider teen, a depressed outsider twenty-year-old. My twenties were full of confusion and yearning, my thirties a blur of depression and marriage and child-rearing. A lot of stuff happened and a lot of stuff was accomplished, but through most of it I felt like I was sleepwalking. At forty I stirred, my eyelids fluttered, light filtered in. At forty-five I sat up and looked around. I see. Okay.

Fifty I greeted not with dread but with exhilaration; I knew who I was, I knew what I wanted and did not want, and finally I liked myself. I didn’t fear losing my looks because I had grown up thinking I didn’t have any. As a teen and young woman I thought myself fat and ugly; not until I was well over thirty did that hegemonic delusion subside. Somewhere around forty or maybe forty-five I realized that not only was I not ugly, I was actually pretty damn attractive, even beautiful. (Around this time my niece, doing a project for some college class, asked me how “pretty privilege” had impacted my life. I started to protest that I never felt pretty but stopped when she raised an eyebrow. Not being aware of privilege does not negate its power. For that brief moment I felt like a White person.) At first this realization made me sad; in some ways, though not others, youth was wasted on me. Had I known I was beautiful, I would have cut through the world of men like a warrior instead of sneaking around like a beggar seeking alms. But girls who come to womanhood valued for their beauty can learn to lean on that beauty like a cane, atrophying the muscles needed to stand upright. I came to womanhood believing that my brain and not my face would be the source of my salvation. My brain was myself.

This was a gift, in the long run. At fifty my face was wrinkling, my body softening, beginning to sag. But my brain was stronger than ever. Well constructed, meticulously maintained, it was firing on all cylinders, free from the gummy oil of youthful obliviousness and ruinous self-doubt. I threw myself a fiftieth birthday party: three cakes, two changes of outfit, sixty people roaming my house and me not giving a damn. I played the music I wanted and ate the food I wanted and talked to whomever held my interest until they didn’t. I danced and danced and danced. I was not afraid of turning fifty; I was liberated.

Sweeping the living room the day after my party, I realized I had no memory of my mother at fifty, this new and wonderful age. Had no memory of her taking a step back and surveying her life with satisfaction, no memory of her coming happily into herself. In my memory, my mother is first young, harried, and beautiful, and then suddenly, one day, she is old. What explains this abrupt transition? Part of it, probably, was my own selfishness. During those middle years of my mother’s life I was preoccupied, focused on my work and my depression and my marriage and my children and my own monkey mind. I checked in on my mother from a distance, both geographically and emotionally. I thought the best thing I could do for my mother was not add to her considerable burdens. By leaving her alone I was helping her. So I told myself.

My navel-gazing probably explains part of this, as does the fact that in her sixties my mother developed a serious illness, one I believe was caused in part by the stress of her life. But even before that my mother seemed older than she actually was. Older than my ex-mother-in-law, for example, though she was, in fact, younger. Older than a White woman friend from my church.

Sometimes people ask my mother’s age. In the first part of your life, people ask you how old you are, then they ask the age of your children, and finally they ask the age of your parents, if your parents are still alive. Sometimes people ask my mother’s age and I give it, followed by a qualification. She’s 83 but it’s really more like 120. She’s 84 and it’s amazing she’s still alive because life for her has been no crystal stair. She’s 85 but it’s a hard 85.

Some people age like trees, well tended and watered. A tree grows from seed to sprout to sapling to mature to elderly to snag. Most trees spent the bulk of their years in maturity, bearing fruit or acorns or pecans or pine cones, seeking only to reproduce themselves. Left alone, certain species of oaks can produce for three hundred years before spending another three hundred in a gentle decline toward death.

Some people age like trees, and some people age like animals, each year compressed. Some people’s years are like animal years not because those people are “animals” (well, all people are animals, but you know what I mean here) but because of how they’re treated by life. Some people age like trees because they live in a forest, and some people age like animals because their world is a zoo.

. . .