Assistant Managing Editor Bess Winter: Here at CR we spend a lot of time reading excellent fiction, poetry, and non-fiction—but what about other forms? Proposed to you today: the humble sign. Utilitarian and often overlooked, the sign points us in a new direction, assures us that we’ve arrived, or even makes us stop and notice things we wouldn’t otherwise—much like great writing. A sign can be garish or understated. It can be illuminated. It can be hand-painted or laser-cut. It can attract or it can repel.

Sometimes when going about my daily life, I come across a sublime sign. This happens especially often here in Cincinnati: a city that never, ever, throws out its old crap. Cincinnati—out of whose horseshoe-studded mud emerges smutty nineteenth-century breweriana, crooked mansions and crumbling row houses, Proctor and Gamble factory flotsam, Prohibition-era tunnels and nooks, petrified remains of Pete Rose trading cards, waxy shards of King Records, the bullet that paralyzed Larry Flynt, and the crinkly stubs of Jerry Springer’s checkbook—is the Rome of Ohio. It’s full of old signs, functional and defunct. We live in the shadow of history, here, and we’re just trying to get to Kroger.

The impulse on encountering one of these signs is to share it with those who will appreciate it—and, so, this column. Each installment will focus on one sign of note, mostly local but also some from far-off. If we could receive submissions of signs as miCRo contenders, these are signs I would publish.

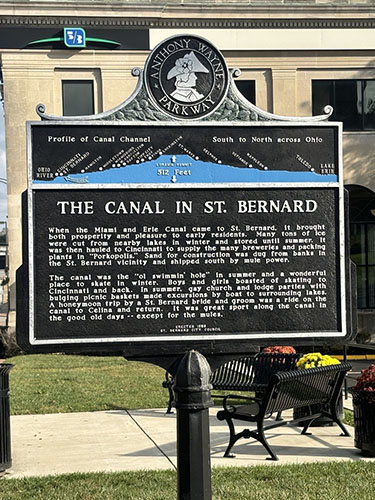

Wordplay and whimsy are afoot on this delightful historical marker in my neighborhood, erected in 1959 by the St. Bernard City Council. I first encountered it while walking my dogs, who had no opinion on it whatsoever. But this human was drawn in immediately by the plosive alliteration, in the very first line, of “prosperity and pleasure,” followed closely by the haunting image of giant blocks of ice floating down the once-bustling Miami and Erie Canal (it has been filled in and is now just a parkway that loops through the city, a shadow of its former self) right into downtown Cincinnati to cool just-butchered meat swinging on hooks and beer brewed by nineteenth-century Germans with generous mustaches.

The second paragraph is where this sign really shines. “The canal was the ‘ol swimmin’ hole’ in summer,” it begins, “and a wonderful place to skate in winter. Boys and girls boasted of skating to Cincinnati and back.” (For context: St. Bernard was, and still is, an independent village that was at one time at a distance from the city and is now surrounded by the city on all sides.) Where the colloquiality of “the ol’ swimmin’ hole” and the image of children on curly-bladed ice skates could be read as too saccharine, a Rockwell-era portrait of the olden days, we’re quickly distracted by the next two lines: “In summer, gay church and lodge parties with bulging picnic baskets made excursions by boat to surrounding lakes. A honeymoon trip by a St. Bernard bride and groom was a ride on the canal to Celina and return.”

“Bulging picnic baskets”: a phrase that simultaneously invites you to lift the gingham cloth and warns you away. Bulging: a very particular word choice. I’m reminded of the threat of botulism, or the scene in the 1991 film The Addams Family in which the family, seated at the dinner table, watches Wednesday try to stab the meal on her plate: a moving blob cloaked in an oatmeal-like sauce. A vague sense of foreboding ensues.

There’s also something terribly disappointing-sounding about your honeymoon being a boat ride up and down a filthy commercial trade route. It says something about the marriage. A simple google search puts the sentence in context; that honeymoon ride would have ended at Grand Lake St. Mary’s—a shallow artificial lake that supplied the canal with water and became a recreational draw for factory workers and laborers in Dayton and Cincinnati. Though I’m usually a completist, I appreciate the lack of historical context here. It’s the right authorial choice to lead into the final line—the superb final line: “It was great sport along the canal in the good old days—except for the mules.”

“Except for the mules”! Rarely does the Aristotelian reversal serve a piece so well as it does here, upending all that’s come before. Imagine everything above: romantic boat ride, ol’ swimmin’ hole, ice skating scenes out of a print by Currier and Ives, church picnics, creaking blocks of ice—all haunted by the presence of mules pulling the boats, braying, farting, etc. And, of course, mule drivers yelling, cracking whips, cursing in German. All the charm is drained from the scene—and, yet, wouldn’t it be charming to live in a place where a packet pulled by a mule was a daily sight, for mules to be your biggest source of stress? Anemoia—a sense of nostalgia for a time we never experienced—sets in. And it does so in layers, because I’m also nostalgic for the 1950s historic imagination that gave birth to this sign. The idea that back in the mid-twentieth century a committee of Ohioans (I envision them all in pleated pants and Donegal tweed skirts, seated around a table) with the mission of preserving an idealized past thought these little details were important enough to stamp onto a sign charms me. We have to mention the darn mules. In this vision everything is in Technicolor, as if working-class St. Bernard, Ohio, is about to be visited by Harold Hill. Workers at the nearby Ivory soap factory break into song, performing heroic leaps over vats of bubbling lye. Somehow, Dick Van Dyke is there.

No cute historical tidbit was too small or too niche for the atomic-era zeal for retelling American history of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, which reached its zenith with the much-misunderstood “midcentury colonial” décor trend. So it is, here, with the mules. Historical inaccuracy was par-for-the-course in the era of Bonanza, and it presents itself in the embellishments on this sign as a written answer to wood-paneled basements with shuffleboards laid into the floor, Remington cowboy prints shellacked onto TV trays: things that, coincidentally, you also find a lot of in Cincinnati.

A bold move, casting this little taste of winking cynicism in iron (or aluminum—what are these signs made of?) so generations to come, passing by on a dog walk or on the way to the barber, would be haunted, too, by mules. That’s life, isn’t it? You may be having a gay old time, but there’s always a mule somewhere.