In our Issue 19.1, we feature Katie Berta’s poem “[To be a child again.]” As part of our blog series From Our Contributors, she explains the background behind that poem, including how two photographs became key to her interaction with her memories as she thought about this post.

You can listen to Katie read the poem here as well:

Katie Berta: “[To be a child again.],” which appears in The Cincinnati Review Issue 19.1, is a part of my manuscript-in-progress, which I’m currently calling collective. The project is a verse novel told by a woman who’s been absorbed into a cult or a commune. Most of the poems in this manuscript are fictionalized—I’ve never been a part of a cult—but some details are drawn from life.

In this poem, the mother who appears is not my mother, but the gravestones in the garage were real. The family who’d lived in our Ohio house before us had two little boys who were about the same ages as my sister and I, and they’d created gravestones out of two-by-twelves, one with the name of each member of their family. They’d left them in the garage when they’d moved away.

In school, I took the place of the older brother, Seth. He handed over his desk and shook my hand, very sweet and friendly, when I visited Mrs. Douglas’s second-grade classroom at Gordon Dewitt Elementary. At home, I moved into his room, its ’90s wallpaper border a circus theme, marginally more mature than the babyish blue koalas that were in my sister’s room. We even looked alike in some ways—he and I were fair skinned and blond while my sister was dark haired and olive skinned, like my dad had been as a kid—and also Seth’s brother.

Years later, Seth, my analog, was killed at their new house when the horse their family owned bolted for the barn. He was thrown off and crushed under its hooves. Our neighbors, who’d been down to visit them since they’d left, let us know. They’d gone to his funeral and had left stones on his grave, a Jewish tradition. I was ten and taking riding lessons at the time—but my mom had me pulled right out.

My parents moved to Indianapolis around the time I left for college, so I haven’t been back to the house I grew up in since I was a kid. When I visit them to find pictures of it, my dad asks, “Were you freaked out by that,” by the weird ways I was inserted into Seth’s life? He admits he was bothered but didn’t want to ask me then, lest he freak me out too.

My parents don’t quite get it—they say, “We took pictures when we were in Akron for the Beacon Journal reunion.” They could just send those? No, no—I want prints from that time.

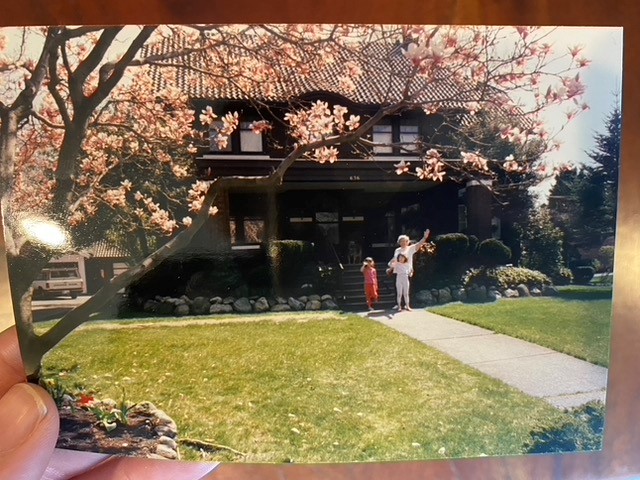

This is my grandma, my sister (in the pink), and me (with the grimy knees) in front of that house. The magnolia tree in the front yard was perfect for climbing, with its low horizontal branches.

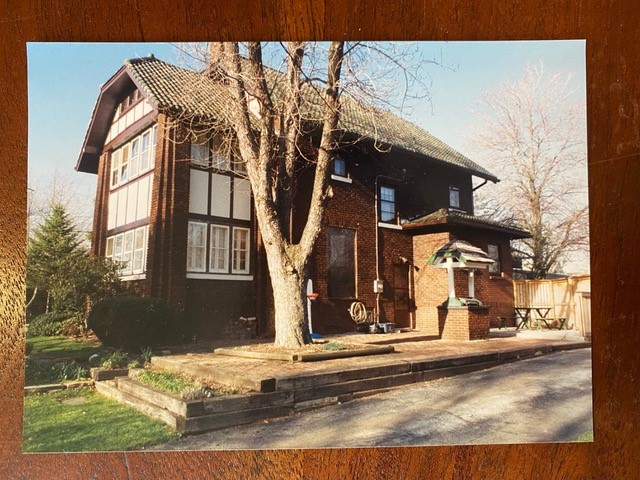

And this is the back of the house, where we played. That wishing well is actually a grill. And that pile of bricks against the wall just to the left of the tree trunk was full of gigantic wolf spiders.

I like the tactile, thing-y quality of these photos (notice how they’ve faded and the dust visible in their shadowiest parts) because that is the quality of my childhood. I guess we do blast off into space in adulthood—the baby-insight in this poem—and never return to full thinginess. When I think of that, of the way I was and the things I’d do (becoming totally absorbed in the dust particles floating in a beam of light in our living room, brushing my hand through the leaves of any plant I met on my walk to school), I could cry. Half the creatures that appear in these photos have died, including my grandmother and my grandparents’ German shepherd on the front porch. Someone else—a stranger—lives in this house now, and I have no reason to return, though it is my most potent home. Childhood, in other words, is bitter nostalgia. The remnants of these experiences do more than linger—they are material, animal in their life.

Katie Berta is the managing editor of the Iowa Review. Her poems have appeared or are forthcoming in Kenyon Review Online, Prairie Schooner, Yale Review, Massachusetts Review, and Black Warrior Review, among other magazines. You can find her book reviews in APR, Harvard Review, Ploughshares, and elsewhere.