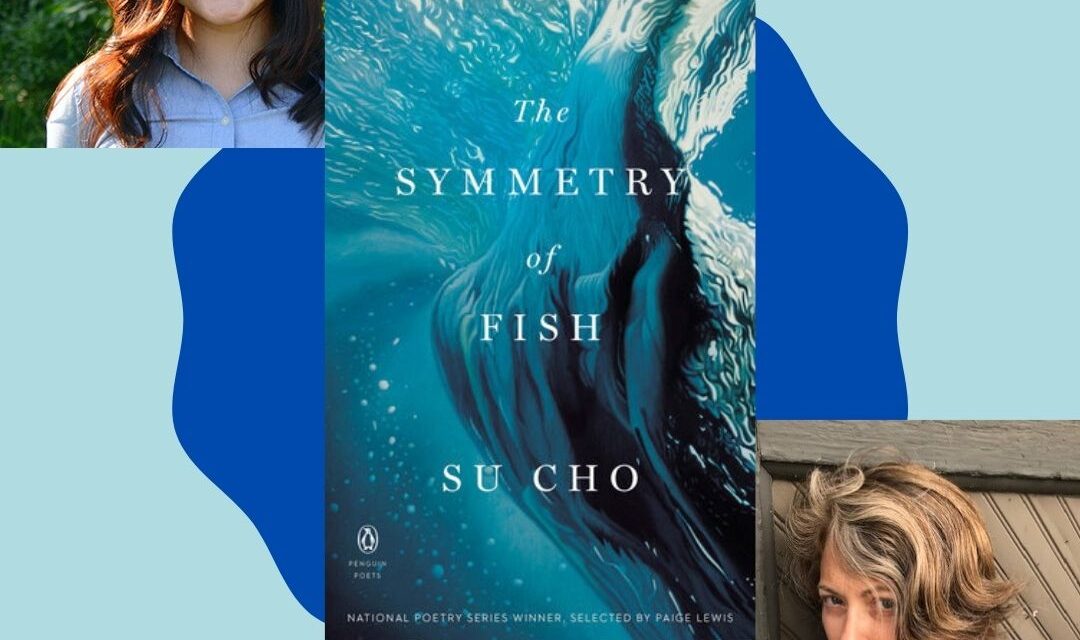

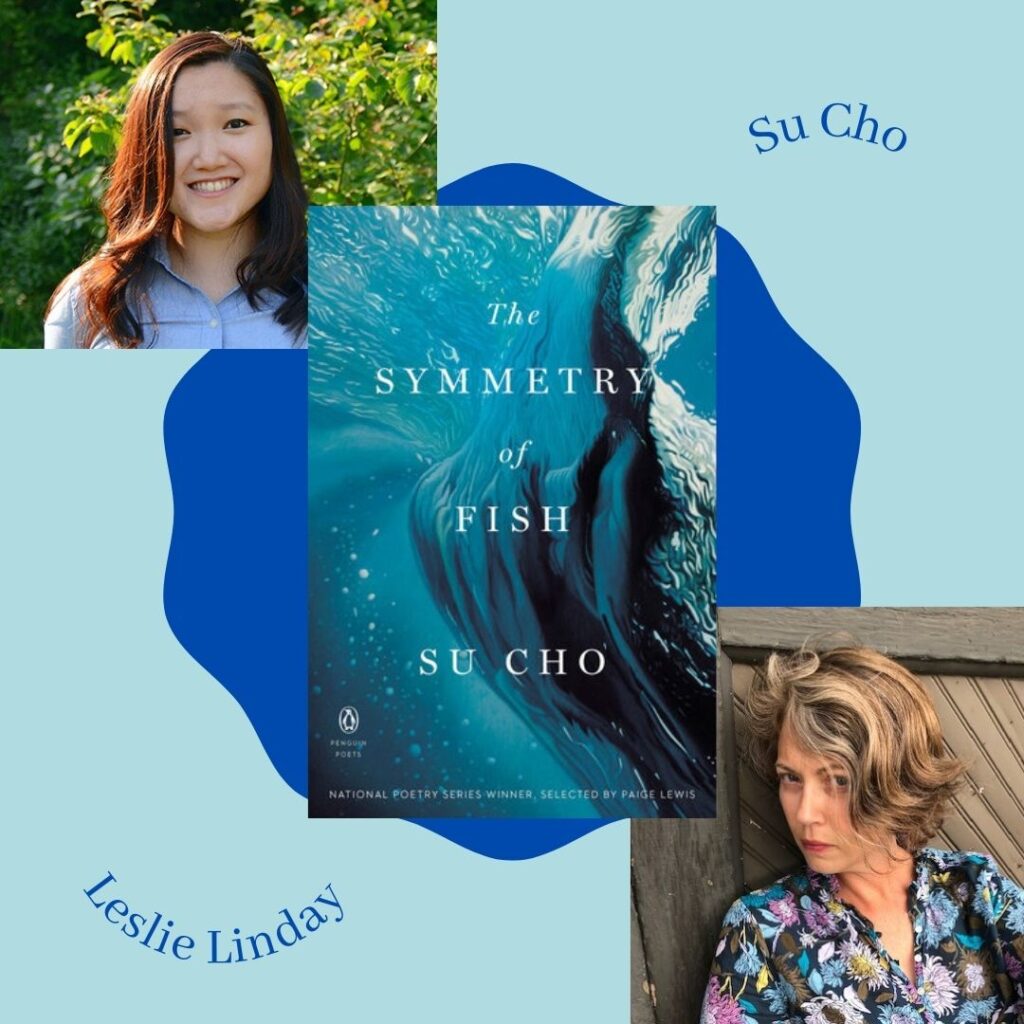

Editors’ note: When Leslie Lindsay reached out to us with an interview of our contributor Su Cho (see her work from our miCRo series here), we were glad to host it on our site and share it with our readers!

Guest Interviewer Leslie Lindsay: Su Cho’s debut poetry collection, The Symmetry of Fish (Penguin Poets, 2022), a National Poetry Series winner selected by Paige Lewis, is a moving debut about coming of age in a Korean American family, as well as about immigration, memory, and a family’s lexicon. It’s at once deep but slippery, a way of holding in while letting go. Cho’s intuition as a writer is lyrical yet visceral; the speaker is both a deep observer and collector as she shapes new meaning and tradition, and blurs boundaries. I am struck by how Cho is continually in the process of acquiring insight rather than dispensing it. Juxtaposing Korean and English, ocean and prairie, parent and child, Cho’s poetry, like water, takes an unpredictable path. I asked her about this quality in her work and more in the following interview over email:

Poetry pauses time. It distills a moment so one may gaze at it objectively, like you do with tangerines and fish bones and wisdom teeth. The Symmetry of Fish is about not just a pause but a reaching back—to your ancestors, their stories and voices left untold. Can you talk about that, please?

Thank you for the insightful approach to the book, Leslie! I appreciate that distinction between pausing and reaching back. There’s a quote from Mei-mei Berssenbrugge that helped me think about this recently. It’s from her poem “Nest”:

A margin can’t rot, no bloated outline around memories of witness, the way origin in the present is riddled with holes.

Mei-Mei Berssenbrugge, “Nest”

I think of the phrase “the way origin in the present is riddled with holes” and how it suggests that there’s an origin in the present, and perhaps in the past and future as well. I imagine that the holes are places where poetry can travel through sound and memory. Every time I work on a poem, my origin shifts just enough for there to be a different perspective, and I imagine that changes my reaching back toward the anchor points of my personal histories.

In this collection, you examine the gap between culture and identity; a mother refuses to take a call from a census taker who requests an adult of the household answer their queries. In “Wisdom Teeth,” there also is a bit of false translation: poignant, but also amusing, relatable. These poems lured me in—I wanted to know how the interaction between parent and child, speaker and reader, would pan out. Was this your intention?

Yes, absolutely. I’m grateful you teased these connections out between those poems! The little gaps in communication open up such vast opportunities for you to fill it in with what you know. It’s interesting to me because parents or any adult figure are supposed to fill those gaps for you, and the poems celebrate the moments the gaps aren’t filled in by someone else—sometimes it’s sad, sometimes it’s good. And the way you fill in the gap can change every time, which is the way I think about my relationship to English and Korean. When the gaps make me uncomfortable, that’s when jokes come into play—like at the end of “Wisdom Teeth.”

Tiny—tine—elements, especially when accumulated into patterns, add up to big effects. There’s white space, yes, but also big, oceanic swells, fish and bones. What I think this might speak to is the way phrases, images, and narratives are passed down in immigrant families. Can you share more about the patterns—themes—motifs—you chose in this collection?

Tine! What a fantastic word. The more I think about it, the more I realize that I was (and still am) drawn to these images because of the possibility of danger. Fish bones and splinters can all get stuck in the body, but when that happens, it’s accidental. There’s a game of chance with those, and that’s how I see memory. There’s a chance that what you recall will be un/pleasant, but you still need to digest the memory. Perhaps it’s like I’m daring myself to use those images again and again to see if something will sting.

What I find so sublime is not just your ability to observe details but your ability to cut through time and space, reaching back to the ghosts of your ancestors, allowing the unspeakable, the hidden, to be revealed. It seems it could be a little magical, a conjuring, or perhaps a meditation. Can you share a bit of your process?

The poems in the collection about the past, especially thinking of my grandparents, are the ones that took the longest. Some of those poems took, no joke, five years to write into their current forms. Sometimes I had to wait a few months or a year to come back to what I wanted to say, and it kept changing. I finally let myself ask questions instead of trying to come up with answers: Why is it that I can’t let this go? Why does this still matter to me?

I was stubborn about the poems at first, that’s for sure. That’s why it took so long for me to ask such a simple question to myself. But that’s the problem when you want to honor a person or a memory. There’s so much pressure and responsibility tied to it that it can start constraining the poem.

Finally—language, the building block of all narrative, is bodily. It must originate somewhere. And biologically, it does (larynx, throat, mouth). Voices infiltrate me. They become part of my skin, my bones, my experience, maybe even my legacy. Words don’t really die; they thrum with life. What happens when we cannot recall a phrase, a definition? Is it about invention or memory—a blurring of both?

What a beautiful way to put it. I love how you say “It must originate somewhere” because it does. When we can’t recall a phrase or a word, our bodies remember for us.

This is a common phenomenon—when you’re with someone you’re close with and all you have to say is “remember that thing . . . what was it called,” and the other person immediately jumps in and knows what you’re talking about? I think that’s our relationship with our bodies remembering for our present self. If I had read what I just said a few years ago, I would have laughed at myself! But how else can we explain it?

It’s like returning to a place you once lived. Even if the people, stores, colors of the buildings have changed, the streets are still there. Don’t we sometimes dare ourselves to close our eyes and see how long we can go before missing a turn?

Leslie Lindsay‘s writing has been featured in or is forthcoming from The Smart Set, Brevity, The Rumpus, DIAGRAM, Autofocus, and many others. She resides in Greater Chicago and is at work on a memoir excavating her mother’s mental illness through fragments. She is a former Mayo Clinic child/adolescent psychiatric RN and can be found on Twitter and Instagram where she shares thoughtful explorations and musings on literature, art, design, and nature.

Su Cho is a poet and essayist born in South Korea and raised in Indiana. She has served as the editor-in-chief of Indiana Review and Cream City Review and as guest editor for Poetry magazine. Her work has been featured in Poetry, New England Review, Gulf Coast, and Orion; the 2021 Best American Poetry and Best New Poets anthologies; and elsewhere. A finalist for the 2020 Ruth Lilly and Dorothy Sargent Poetry Fellowship, recipient of a National Society of Arts and Letters Award, and a two-time Pushcart Prize nominee, she is currently an assistant professor at Clemson University.